History has long been among the casualties in the country’s long cultural war over abortion, according to Marvin Olasky, author of the new book, Abortion Rites: A Social History of Abortion in America (Regnery, 1992).

The accepted wisdom today, repeated from news decisions, is that abortion has been widespread and widely tolerated throughout much of the country’s history. According to that view, Americans have a long tradition of moral indifference to abortions performed in the first four or five months of pregnancy, and those states which began regulating abortion in the mid–19th century did so only when pressured by doctors’ groups to protect women from unscrupulous and unsafe abortionists.

The U.S. Supreme Court adopted that reading of history in Roe v. Wade, its 1973 decision overturning state abortion statutes and establishing a constitutional right to abortion. That reading was later affirmed in the only scholarly history of the subject, Abortion in America (Oxford, 1978), written by James Mohr, a pro-choice historian under “population policy” grants from the Rockefeller and Ford Foundations.

“I always felt it was a shame that Mohr’s was the only book on the history [of abortion] and that it was always being cited by the Supreme Court and in the newspapers and that pro-lifers had nothing to go up against it,” said Olasky, a Presbyterian who teaches journalism at the University of Texas in Austin, in a recent interview.

Until Abortion Rites, which was funded in part by the Chicago-based Americans United for Life, Mohr’s scholarship had gone largely unchallenged. But, while writing and earlier book, The Press and Abortion, 1838–1988, (Lawrence Erlbaum, 1988), Olasky found that much was missed by Mohr’s near exclusive reliance on the texts of abortion laws, legislative debates and interest group reports.

By tilling the cultural soil of the 19th century—newspapers, journals, speeches, sermons and popular books—Olasky uncovered a broad range of sentiments that belie Mohr’s claim that Americans were morally neutral about abortion.

Drawn from staunch Calvinist stock, American colonists inherited the 16th-century Protestant reformer’s view that the fetus, “though enclosed in the womb if its mother, is already a human being” and should never be “rob[bed] of the life which it has not yet begun to enjoy.”

Olasky found numerous popular sermons and tracts in which abortion is condemned. “Wilful murder” was what one 1671 midwives’ manual called it. Abortion, it seems, was the last resort for a small number of abused women—either servants forced into sex by their masters or women seduced and abandoned by their lovers. They used or were compelled by the lovers to use the handful of herbal abortifacients—potions which could be ingested to induce abortions—then available in the colonies.

Olasky marshals evidence to suggest that colonial juries and courts sought to protect both the mistreated woman and the life of the unborn child. In one 1652 case, Maryland prosecuted a prominent advisor to the governor for coercing his 21-year-old bondservant into sex and then forcing her to drink an abortifacient which killed the child and caused her intense pain. Indicting him for having “murderously endeavored to destroy or murder the child by him begotten in the womb,” a grand jury fined him, forbade him from ever holding public office and set his bondservant free.

Unborn life was also recognized in the earliest legal injunction against abortion, a 1716 New York City ordinance barring midwives from suggesting or doing anything “to any woman being with child whereby she should destroy or miscarry” her child.

Civil Wars

Abortion became a “major social problem” during the decades around the Civil War, according to Olasky. “There was a lot of abortion going on, but it was not part of the mainstream of American society.”

Abortion, as he reads it, was primarily the resort of prostitutes and persons caught up in the “free love” and “spiritist” movements of the day. It was said to be a “greater sin” to bring an “unwanted child” into the world “than to kill them before they are born,” a claim made in the popular 1858 book “The Unwelcome Child or the Crime of an Undesired Maternity.”

Abortion became an increasingly lucrative business in this moral and intellectual climate. The country’s richest abortionist, Madame Restell, ran clinics in New York, Philadelphia and Boston; lived in a mansion; dressed in floor-length fur coats; and was chauffeured about New York in a horsedrawn carriage. She hobnobbed with senators and financiers, and boasted that many of their wives were repeat clients of hers.

Mohr’s pro-choice history attributes the rise of anti-abortion laws in this period to the work of the nascent American Medical Association. He contended that the AMA seized on the abortion issue as a way to boost its social standing and political influence, and to drive midwives out of the baby-delivery business.

But Olasky argues convincingly that state legislatures responded more to the abuses of a blatantly commercialized abortion industry that they did to the doctors’ lobby, which in his estimation was weak and politically ineffective.

The country’s first anti-abortion law, passed in Connecticut in 1821, was a direct response to a scandal involving a popular local clergyman who had forced his illicit lover to abort their baby. Likewise, after hundreds gathered in protest outside Madame Restell’s New York City clinic in 1846, the state legislature hurriedly enacted a tougher law regulating abortions.

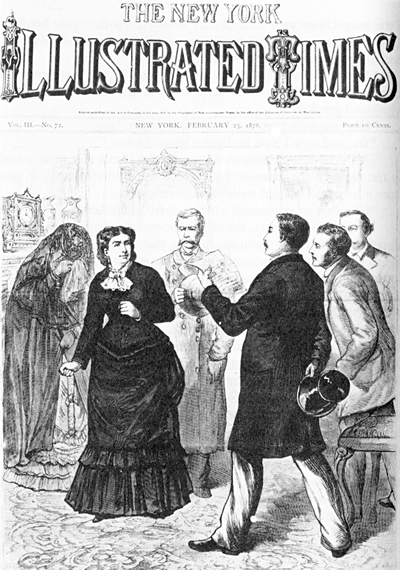

Abortion became one of the social evils taken up by the 19th-century’s “muckraking” journalists, who sought to expose the hidden injustices of their times. Abortionists’ abuses were front page news in lurid tabloids like The National Police Gazette as well as papers of record like The New York Times.

The Times, for instance, editorialized in 1870 against “the perpetuation of infant murder” and complained bitterly that “the lives of babes are of less account than a few ounces of precious metal or a roll of green backs.”

Olasky does agree with Mohr that the nation’s churches were only bit players in the 19th-century crusade against abortion. While the Presbyterian church and individual Catholic leaders went on record as vehemently opposed to abortion, their zeal seldom trickled down to the folks in the pews. Like Mohr before him, Olasky is at a loss to explain the churches’ silence.

Olasky demonstrates a broad base of moral opposition to abortion in 19th-century America, which Mohr’s book ignored or played down.

For example, the AMA’s campaign rhetoric appealed solely to the morality of the “murderous destruction” of abortion and affirmed that life begins at the moment of conception. Feminists like Elizabeth Evans urged the banning of this “dreadful evil” and did the first interviews with women suffering from what is now called “post-abortion syndrome.” Women around the country started hospitality homes and adoption services for unwed mothers and unwanted children.

A few years after the Emancipation Proclamation, a popular Protestant preacher declared: “We have to rid ourselves of the blight of Negro slavery, affirming that no man may be considered less than any other man. Now let us apply that holy reason to the present scandal” of abortion.

The moral tenor of the times could also be heard in the courts, as in the 1871 case in which a New York City judge called abortionists “traffickers in human life” who should be themselves “exterminated.”

Finally, the moral fervor against abortion became the law in much of the land. By 1868, Olasky reports, 30 states had banned abortion, 27 of them banning it at all times during pregnancy.

To show the seriousness of the crime against human life, eight states (including New York) defined abortion as “manslaughter”; Maine made it a crime to “destroy [a] child before its birth.”

Modern Times

The story of the 20th century may be how abortion was made a central component of both the feminist agenda for economic and sexual self-determination and the government efforts to control the growth of the underclass through birth control.

As this century ends, abortion is increasingly and aggressively wielded as a tool of social policy—from the president ordering free abortions for the poor, to lower court judges sentencing abusive men and women to sterilization, from states penalizing poor women for having more children than the state deems appropriate, to public schools distributing birth control devices to children.

The publication of Olasky’s Abortion Rites raises troubling questions concerning America’s public memory—how history is told and who decides what is history. How is it that such a significant and highly relevant historical issue—the country’s attitude toward abortion—has come to be dominated by a single interpretation. It will be interesting to see how history treats Olasky’s version of events.

Originally published in The Evangelist (February 18, 1993)

© David Scott, 2009. All rights reserved.