Leaving Saudi Arabia recently, his mission as U.S. commander in the Persian Gulf complete, America’s newest war hero, Gen. Norman Schwarzkopf, was defiant but on the defensive: “Anyone who dares even imply that we did not achieve a great victory doesn’t know what the hell he is talking about.”

Since the war’s end, a lot of people have been talking about the hell that’s been created in the Middle East: More than two million people are homeless and in search of refuge. Thousands of children and their elders are facing starvation and disease in Iraq, Iran, Turkey, and Jordan; Palestinians are being tortured and executed in Kuwait. Saddam Hussein still rules Iraq, and peace talks between Arabs and Jews broke before they even got started.

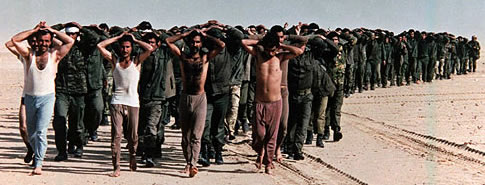

In addition to the concerns about U.S. attacks on civilian and Iraqi society, moral questions are being raised about U.S. tactics during the 100-hour ground battle at the end of the war.

During that single battle, which killed some 50,000-65,000 Iraqi soldiers, allied forces practiced “carpet-bombing” and used the deadly chemical weapon napalm to literally “burn out” Iraqi troops from their positions.

The U.S. attacks continued despite the fact that Iraqi forces were doing just what they’d been ordered to do—leaving Kuwait unconditionally. An Army tank commander told the Wall Street Journal that the U.S. aim was to “beat their … brains in.” Another enthusiastic U.S. recruit likened the attack to “shooting fish in a barrel.”

Their enthusiasm and metaphorical excess would seem to have come from the top echelons of U.S. command. Gen. Schwarzkopf told British television on March 27 that he had wanted to continue “to rain great destruction on” the Iraqis but President Bush ordered him to stop.

But one U.S. enlisted man, sickened by what he’d been asked to do, told the New York Times he would never tell him wife about those 100 hours of ground war. “I do not want her to know that side of me,” he said.

At the barest minimum, the conduct of U.S. warmakers during the ground war raises serious moral questions. One Air Force general justified “the very brutal things” done to the Iraqis as part of “the nature of war.” But, the moral question remains: were Catholics and other soldiers asked by their leaders to participate in a campaign that was morally unconscionable?

Warnings by Pope John Paul II and other Catholic leaders in the region—that a U.S. invasion would only foment simmering anti-Israeli and anti-Western resentments in the region, especially among radical Islamic sects—seem prophetic in light of the war’s outcome.

The war has already stirred up long standing religious and ethnic tensions in the region, as the rebellions of Iraq’s Shiite Muslims and Kurds indicate.

The $43-billion war did nothing to address the underlying causes of instability in the Middle East. Indeed, it seems to only have aggravated the imbalance of wealth and power and the conflict between Arabs and Jews.

A 30-member coalition of international aid agencies, including the U.S. bishops’ Catholic Relief Services, questioned whether Israel used the war as an excuse to tighten the screws of its occupation in Palestinian territories. The around-the-clock curfew imposed by Israel in the occupied territories pushed Palestinian industry and agriculture “to the point of bankruptcy,” the group concluded. The curfew has left nearly 80 percent of the population there out of work. When the curfew was finally lifted, many found they had been fired for “absenteeism” by their Israeli employers.

In Kuwait, the end of the war has seen Kuwaiti military officials, with the assistance of U.S. special forces, dispensing violent justice against Palestinians who opposed the war and against groups seeking democratic change in the country. Middle East Watch, a New York-based group, claims that U.S. officials were present during some nearly 200 execution-style killings of Palestinians in Kuwait since the fighting stopped.

Moreover, at the same time it is preaching peace, the Bush Administration and Congress recently gave Israel millions of dollars to build new settlements for Jews in the occupied Palestinian territories—a blatant violation of United Nations resolutions that can only lead to greater injustices, tensions, and resentments.

A War of “Good Versus Evil”

Nonetheless, in the aftermath of war, President George Bush, too, has been on defiant but defensive. The 43-day war in the Persian Gulf was not only a great military victory, but a moral one as well, the President insisted in a recent interview with religious journalists.

Mr. Bush continues to maintain that the war was one of “good versus evil,” and that “the turning back of aggression and the way we did it was morally correct.”

Religious leaders who criticized the war as immoral, such as Pope John Paul II and scores of the world’s Catholic bishops, “missed the point,” he said. The war “worked out differently than some of these people predicted,” Mr. Bush boasted.

But, with the easing of military censorship and the ebbing of understandable if at times euphoric wartime patriotism, evidence has come to light which casts doubt on Mr. Bush’s moral reading of the war. The record that is emerging—from testimony by government officials, independent international studies and news accounts—indicates that religious critics were on the mark in questioning whether the war was just or justifiable.

First, it would seem that the U.S. bishops and others were correct in questioning whether the stated U.S. policy of liberating Kuwait was, in fact, the real reason for going to war with Iraq. Since the end of the conflict, new information has come to light on what the Reagan/Bush Administration in the early 1980’s called America’s “special relationship” with Iraq. Also, post-war developments have offered new insights into U.S. strategic interests in the religion.

The evidence now seems to suggest that the U.S. war against Saddam Hussein was waged to punish a disobedient client dictator and to establish a key military outpost in the Third World. Gen. Schwarzkopf admitted as much when the ceasefire was announced on Feb. 27. “There’s a lot more purpose of this war than just get the Iraqis out of Kuwait [sic],” he said.

Underlying U.S. goals are reflected in the post-war “regional security” pact, which will give the U.S. a new military outpost on the Gulf island state of Bahrain. “We have always been anxious to have a forward headquarters in the region, and I think we may be able to get one at this time,” said Gen. Colin Powell, head of the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff.

The outpost is a key to U.S. military strategy in the post-Cold War world. That was indicated in remarks made recently by Defense Secretary Dick Cheney about the closing of U.S. military bases. The U.S. must shift from a policy oriented towards the defense of Western Europe from a possible Soviet attack, he said. Now the U.S. must prepare for “regional contingencies” in the Third World, such as the Gulf War, which he characterized as the “conflict in Southwest Asia.”

As with its December 1989 invasion of Panama, the U.S. ends the Gulf War with a new military command post located at a strategic gateway to the Third World. The conquest of Panama gave the U.S. military access to South America and the Pacific Rim. The spoils of the Gulf War—the new U.S. headquarters in Bahrain— will give the U.S. the military capability to police Africa and Asia.

Indiscriminate Weapons

President Bush and his generals made a point in early speeches and press briefings of saying that the war was being conducted “morally” and with careful attention paid to protecting civilian lives.

“We are a moral, ethical people,” Gen. Schwarzkopf insisted on Feb. 4. In addition to the professed morality of U.S. policy, much was made of the supposedly pin-point accuracy of precision-guided “smart” missiles used by the U.S., missiles which would hit military targets while sparing civilian populations.

But information that has come to light since the war’s end has called into question both the accuracy of U.S. weapons and the morality of the U.S. attacks. In congressional testimony after the war, a former assistant secretary of defense charged that the president and the military had “shamelessly doctored statistics” and even “hand-selected video clips of isolated successes” to create the illusions of a war in which only military targets were struck.

Only seven percent of the bombs dropped on Iraq and Kuwait were actually “smart” missiles, and 90 percent of those were accurate. However, the vast majority of all U.S. missiles—a staggering 70 percent of the 88,500 tons of munitions dumped on Iraq and Kuwait—missed their targets.

There is also evidence to suggest that the U.S. knew beforehand that many of its so-called “surgical” air strikes on Iraqi cities wouldn’t hit their military targets. In fact, it was disclosed during this war, that dozens of supposed “smart” bombs had been misfired in the Panama invasion, resulting in immense civilian casualties.

There are no hard figures on the numbers of Iraqi civilians killed by the allied bombing raids. Saudi sources put the number at 100,000 killed or wounded. The U.S., which voiced so much concern for protecting civilians during the fighting, has been strangely cool and indifferent to reports showing massive numbers of innocents killed. “It’s really not a number I’m terribly interested in,” Gen. Powell remarked on Feb. 23.

Total War

Whether or not U.S. war planners intentionally targeted civilians, some would characterize the U.S. policy as one of “total war,” a tactic deplored in official Catholic teaching. Iraq’s roads, bridges, utilities, communications, and energy utilities were defined as “military” targets and were subjected to more than 100,000 bombings. Under such a strategy, the moral concept of “civilian immunity” is rendered virtually pointless.

U.S. attacks, according to United Nations’ investigators, resulted in the “near apocalyptic” devastation of Iraqi society. “Most means of modern life support have been destroyed or rendered tenuous,” the U.N. mission reported. In addition to the countless civilians killed, the U.N. team counted at least 9,000 Iraqi homes completely destroyed and 72,000 left homeless. “Iraqi rivers are heavily polluted with raw sewage” and streets in villages have been reduced to “pools of sewage,” the mission reported.

Similar findings were made by the International Red Cross, the World Health Organizations, UNICEF, and Doctors Without Borders. U.S. attacks reduced Iraq’s water supply by 95 percent, and there are initial signs of a cholera epidemic and high incidences of other children’s diseases caused by poor diets and unclean drinking water. Food rations for an average adult are less than one-half of what is needed to sustain a healthy five-year-old child.

Two months after the war, there are still acute shortages of medical supplies and those Iraqi hospitals which survived the attacks are having to turn away persons needing assistance. Iraq, the U.N. said, had been bombed into the “pre-industrial age.”

The bombings and the continued economic sanctions against Iraq have left the people without any means to power basic equipment such as refrigerators, hospital instruments, and irrigation and sewage treatment facilities.

Iraq’s farm lands have been ruined, according to the U.N., and “barring a rapid change in the situation, widespread starvation conditions become a real possibility.”

A World Order Not All That New

Rather than bringing peace and order to the world, there is evidence that the Gulf War triggered a new round in the militarization of the planet. In the war’s aftermath, Third World nations are girding themselves for the next generation of high-tech wars, and Western arms suppliers are lining up eagerly to fill up their orders for high-tech weapons.

The Congressional Research Service and the U.S. naval intelligence corps have testified in recent weeks that nearly 40 Third World countries have approached the U.S. seeking to buy some of the advanced offensive and defensive weapons on display in the Gulf War.

President Bush has asked the Congress for permission to underwrite the export of $1 billion worth of U.S. arms to its allies around the world. In addition, he wants Congress to approve $33 billion in new weapon sales to the Middle East—with most of that money going to arm Israel, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia.

For all Mr. Bush’s high-toned talk about a “new-world order” in which the sovereignty of nations and human rights are respected, there are questions about whether his America is living up to the moral standards it is preaching to other nations.

We now know that a radio station linked to the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency incited the abortive Kurdish rebellion in Iraq, urging the Kurds to undermine Iraq’s sovereignty. In addition, though their secret mission remains shrouded in secrecy, it has been reported that the U.S. Special Forces, the nation’s elite guerrilla warriors, are at work in Kuwait and Iraq. Their role has not been disclosed by the U.S., but a New York Times reporter witnessed a special forces member supervising the beating of a Palestinian by Kuwaiti paramilitary police.

Since the war’s end, word has leaked out about the Bush Administration’s failed covert attempts to foment insurgency in Libya and to topple that nation’s government. It has also been learned recently that, prior to the 1980 U.S. presidential elections, operatives in the Reagan-Bush campaign conspired with Iranian leaders to prolong the ordeal of U.S. hostages in order to discredit the reelection campaign of then-President Jimmy Carter.

There is even talk now of America becoming a international policeman of sorts, combating other American-defined threats to the world’s freedom and stability. As a hint of the future, perhaps, U.S. officials recently denounced the belligerence of North Korea and decried that nation as a “nuclear threat.”

Others are talking of the overthrow of Cuba’s communist government. On April 14, under U.S. pressure, the 16 nations of the North American Treaty Organization (NATO) announced that they were committing more than 100,000 troops to the formation of a “rapid reaction force” that would enable them to fight low-intensity wars at a moments notice anywhere in the Third World. Evidence now available from independent international agencies and even U.S. government officials demonstrates conclusively that the U.S. war against Iraq was not waged for moral reasons or conducted according to moral principles.

This evidence suggests that politicians and military leaders knew that three-quarters of their weapons were missing their targets and killing thousands of innocents. Still, they assured the American people that they were “moral, ethical people,” and weren’t targeting civilians.

The nation’s free press and the overwhelming majority of the populace accepted, without much question, full military censorship and a series of untruths told by their national leaders. And no one seems to mind too much that those heart-wrenching tales Mr. Bush told about Iraqis yanking Kuwaiti babies from incubators were fabricated by U.S. propagandists.

Larger moral questions face Catholics in the wake of the Gulf War. The Church’s moral tradition recognizes the right of nations to go to war, but only as a last resort and only in self-defense or in the defense of others against extreme injustice. Even then, the prosecution of war can only be justified if the war meets a certain moral criteria.

In light of what is now known about the conduct of the U.S. in the Gulf War, two basic questions are raised about the continued validity of the Church’s “just war theory” in providing moral guidance to Catholic soldiers and citizens:

First, given the proven inaccuracy of the world’s most advanced weapons systems and the seemingly unavoidable temptation to escalate to “total war,” is it practically possible to wage a “just war”—one that discriminates between aggressors and innocents, one that is “proportionate” in the destruction it inflicts?

Second, given the apparently deliberate abuse of “just war” rhetoric by U.S. leaders in the Gulf War, can Catholic soldiers and citizens trust that their leaders are committed to waging war for real abuses and operating according to ethical principals?

Those large questions need to be answered before the next war begins.

And that next war is coming. The “national energy strategy” floated recently by the Bush Administration shows that the nation has no intention of weaning itself from dependence on foreign oil and little interest in developing renewable energy sources. That unwillingness virtually promises the U.S. will be entangled in future “resource wars” in the Middle East and Third World.

President Bush was telling an ironic truth when he said in his March 6 address to Congress: “The victory over Iraq was not waged as ‘a war to end all wars.’”

Originally published in The Evangelist (May 2, 1991)

© David Scott, 2005. All rights reserved.