Lesson Goals

- To read the New Testament with understanding.

- To understand how the New Testament depicts Jesus as the fulfillment of the covenants of the Old Testament.

- To appreciate, especially, the importance of God’s everlasting covenant with David for understanding the mission of Jesus and the Church as it is presented in the New Testament.

Lesson Outline

I. Review and Overview

A. The Covenant Plan Fulfilled

With the coming of Jesus, the story of God’s covenant plan reaches its conclusion.

Jesus “fulfills” the promises of each of the five covenants we have been studying in this course – the covenants with Adam, Noah, Abraham, Moses and David.

What do we mean by covenant fulfillment? Each of the earlier covenants was a pledge – an oath sworn by God to do certain things. For instance, in His covenant with Noah He swore not to destroy the world by water again; he swore to Abraham that by his descendants the nations of the world would be blessed.

However, if the Bible ended with the last book of the Old Testament (remember “testament” is just another word for “covenant”) then it would appear that few if any of God’s promises had been fully kept.

Certainly, by the end of the Old Testament, all the world’s nations hadn’t found blessing in the descendants of Abraham. In fact, the descendants of Abraham – the twelve tribes of his grandson, Jacob – could barely be identified. They had been scattered to the four corners of the known world.

God’s final covenant, the one in which each of the earlier ones was to be fulfilled – the “everlasting covenant” with David – seemed hopelessly abandoned as we concluded the Old Testament in our last lesson.

To review: God had made an “eternal covenant” (see 2 Samuel 23:5) with David, promising that He would raise up a son of David to reign on David’s throne forever (see 2 Samuel 7:8-16; 1 Chronicles 17:7-14), and that his kingdom would extend over all nations (see Psalm 2:8; 72:8,11). He had promised that this son of David would be His own son, the son of God (see Psalm 2:7), that he would build a Temple to God’s name and be a priest forever, like Melchizedek, the priest who offered the sacrifice of bread and wine for Abraham’s victory over his enemies (see Psalm 110:1,4).

But after the reign of David’s son, Solomon, everything had fallen apart. The kingdom was divided in two, and the people suffered corruption, invasion and exile. Even when the people were restored from exile, centuries continued to pass without any sign of the great Davidic king that God had promised.

At the time when Jesus was born, there was no kingdom to speak of, no Davidic heir in the wings. Still, the devout awaited the fulfillment of God’s promises, awaiting the consolation of Israel – the coming of the new son of David and the resurrection of his fallen Kingdom (see Luke 1:69; 2:25,38; Mark 11:10; Isaiah 40:1; 52:9; 61:2-3).

B. Turning to the New Testament

But with Jesus comes the fulfillment of God’s oath to David. As we will see, the New Testament shows us the image of Jesus as the “new David” and of His Church as the restored kingdom promised to David.

But we will also see how Jesus is depicted as fulfilling all of God’s earlier covenant promises – He is the new Adam, bringing about a new creation, restoring humankind to the paradise promised in the beginning. He is a new Noah, bringing about a flood that saves, the waters of Baptism. He is the new son of Abraham, in whom all the nations of the world will find blessing. He is the new Moses, giving God’s chosen people a new Passover, the Eucharist, and leading a new exodus, a deliverance from sin, by His Cross and Resurrection opening up the promised land of heaven.

We see three of these earlier covenants referred to in the first line of the New Testament:

“The book of the genealogy of Jesus Christ, the son of David, the son of Abraham” (seeMatthew 1:1).

In its first words, the New Testament points us back to creation, to Genesis, the first book of the Old Testament. The word we translate “genealogy” is actually genesis, a word meaning “creation,” and of course, the name of the Bible’s first book.

We’re also referred in this first sentence to God’s covenants with David and with Abraham. Remember that Abraham’s covenant involved the gift of a son, Isaac, whose descendants were to be the source of blessing for all the earth (see Genesis 22:18).

Finally, Jesus is called “Christ,” the Greek word for Messiah or “anointed one.” This word points us to the covenant with David – the Messiah or Christ was the Davidic figure that many of Israel’s prophets said would be sent to deliver Israel and restore the kingdom to Israel.

So in the first sentence of the New Testament we have an allusion to three of the five peaks of salvation history that we have studied in our previous lessons – Adam, Abraham and David.

And in this sentence, so rich in Old Testament allusions, we have a summary of all that the New Testament will tell us about Jesus: The New Testament is the book abo ut the new world created by Jesus, the Messiah, the promised son of David, in whom God fulfills His promise to Abraham – that in his descendants all peoples will be blessed.

II. The Birth of the Messiah

A. Annunciation and Visitation

Salvation history in the Old Testament reached its climax in God’s covenant with David. We could say that the hope of Israel at the time Jesus was born centered on God’s promises to David.

And we will see as the story of Jesus unfolds in the Gospels that much of the plot and the tension hinges on this question about Him: “Could this perhaps be the son of David?” (seeMatthew 12:23; 20:30-31; 21:9,15; 22:44-45).

In all the familiar scenes of Jesus’ life, we see the Gospels answering that yes, Jesus is the long awaited son of David, the son of God sent to restore the kingdom to Israel.

This is the message of the Annunciation, the announcement of His birth by the angel. Gabriel tells Mary that God will give to Jesus “the throne of David His father, and He will rule over the house of Jacob forever and of His kingdom there will be no end” (see Luke 1:32-33).

What is the angel saying? That Jesus is the son of David, that he will rule over a restored kingdom of Israel (“the house of Jacob”) for all time.

In Mary’s Visitation of her kinswoman, Elizabeth, we again hear echoes of the promises of salvation history.

Mary cries out in song that Jesus’ coming is God’s answer to all Israel’s prayers, a fulfillment of “His promises to our fathers, to Abraham and to his descendants forever” (seeLuke 1:55).

His Mother wants us to know that as the son of David, her Son will fulfill God’s covenant promise to Abraham – that “in your descendants all the nations of the earth shall find blessing” (see Genesis 22:18).

This is stated even more forcefully in the song of Zechariah, Elizabeth’s husband, when their child, John the Baptist, is born (see Luke 1:67-79).

What’s happening, Zechariah prophesies, is nothing less than God visiting and saving His people. He is making good on everything “He promised through the mouth of His holy prophets from of old.”

In Jesus, Zechariah declares, God has “raised up a horn of salvation within the house of David…mindful of His holy covenant and of the oath He swore to Abraham.”

B. Nativity and the Temple

The story of Jesus’ birth or Nativity is also told in a Davidic key.

Luke tells us that Joseph and Mary went to “the city of David that is called Bethlehem, because he [Joseph] was of the house and family of David” (see Luke 2:4). As we saw in our last lesson, it was in Bethlehem that David was born and anointed with oil by Samuel (see 1 Samuel 16:1-13).

Matthew, in his Gospel account of Jesus’ birth, also wants us to know that He is the long-awaited “Messiah” and “King of the Jews” (see Matthew 2:2,4).

We see this in the answer the chief priests and scribes give to the ruthless Herod (seeMatthew 2:5-6). They quote two Old Testament passages (Micah 5:1-2 and 2 Samuel 5:2) to tell Herod that the Messiah was expected from Bethlehem and that he will be a “shepherd” to God’s chosen people.

Even one of our most familiar passages from the Gospel – “Behold, the virgin shall be with child and bear a son, and they shall call him Emmanuel” (see Matthew 1:3) – refers to a promised son of David.

Matthew is recalling a prophecy of Isaiah who, in the period when the kingdom of Israel was divided, served as a prophet to “the house of David,” serving the heirs of the Davidic line (see Isaiah 6-7).

In a time of distress, Isaiah foretold the birth to a virgin of a savior-like king who would be born of David’s line and would be called “Emmanuel,” a name that literally means “God with us” (see Isaiah 7:13-14).

Many believed that this prophecy had been fulfilled in the birth of King Hezekiah, a great and righteous king (see 2 Kings 18:1-6).

Matthew, however, is telling us that the birth of Hezekiah was only a partial fulfillment of Isaiah’s promise. Jesus is the true and ultimate fulfillment.

We hear Isaiah’s voice again in the story of Jesus’ Presentation in the Temple, especially in the song of Simeon.

Simeon sees in Jesus, the “salvation” promised by God. Notice that the promise Simeon sees fulfilled is not only for the chosen people Israel. It is a salvation that is both “glory for Your people Israel” but also “a light for revelation to the Gentiles” – that is, a beacon for all the peoples of the world.

Simeon is invoking here the “universal” or worldwide promises made about David’s kingdom – that the restored kingdom of David would be an international empire stretching to the ends of the earth and embracing all nations and peoples (see Psalm 2:8; 72:8,11).

In an echo of God’s promise to Abraham’ descendants, the Scriptures tell us that by the Davidic King and Kingdom “shall all the tribes of the earth be blessed, all the nations” (seePsalm 72:17).

Isn’t it interesting that the last two stories we have about Jesus’ childhood involve the Temple?

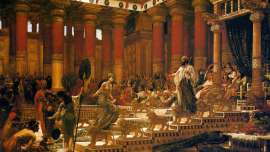

God promised not only that the son of David would be His son, but that this son would build a “house,” a Temple to the heavenly Father’s name. Of course, that promise was partially fulfilled when David’s son, Solomon, built the glorious Temple in Jerusalem.

As the new and true Son of David, Jesus too will build a “temple” to God’s name. That temple will be His body and the Church (see John 2:21; Matthew 16:18).

We see this foreshadowed in the story about Mary and Joseph finding Jesus in the Temple. What does Jesus tell them? Like a dutiful son of David, he replies: “Did you not know that I must be in My Father’s house?” (see Luke 2:49).

III. The Kingdom Is at Hand

A. Baptizing the Beloved Son

The start of Jesus’ “public life” is His baptism in the Jordan River by John the Baptist.

As you read this story, notice the words that are heard from the heavens: “You are my beloved Son, with you I am well pleased” (see Mark 1:11). The words echo the promise that God make to David’s son – that he will be God’s son and that he will rule the nations (see Psalm 2:7-9).

Following His baptism, Jesus is driven into the wilderness to be tempted by the devil.

Here, we see emerge another theme in the Gospel’s presentation of Jesus. Jesus as the new Moses, the representative of the new Israel, the new “beloved son” of God (seeExodus 4:22).

This identification of Jesus actually starts early in Matthew’s Gospel. If you look closely you will notice a lot of parallels between the early life of Jesus and the early life of Moses.

Herod kills all the Hebrew male children at the time of Jesus’ birth. Pharaoh, at the time Moses was born, also ordered all the Hebrew baby boys to be killed (see Exodus 1:15-16;Matthew 2:16-18).

Moses was rescued by a family member (see Exodus 2:1-10). So is Jesus, carried off by Joseph to – of all places – Egypt, where Moses, the first deliverer of God’s people, was also raised (see Matthew 2:13-15; Exodus 2:5-10).

Like Moses, Jesus too is called back to his birthplace after a time of exile (see Matthew 2:20; Exodus 4:19).

Moses liberated the Israelites, leading them on an “exodus” from Egypt. Jesus’ Baptism in the New Testament is the beginning of a a “new exodus.” Like Israel, he is declared God’s “beloved Son” and is made to pass through water (compare Matthew 3:17 and Exodus 4:22; Psalm 2:7; Isaiah 42:1; Genesis 22:1).

Israel, after crossing the Red Sea, was driven into the desert to be tested for forty years. Jesus leaves the baptismal waters of the Jordan and is driven into the desert to be tempted and tried by the devil for forty days and nights (compare Matthew 4:1-2 and Exodus 15:25;16:1; see also Deuteronomy 8:2-3; 1 Corinthians 10:1-5).

Is it just coincidence? Not a chance. Let’s look carefully at the story of Jesus’ tempting in the wilderness (see Luke 4; Matthew 4).

B. Tempting the New Moses

In the desert, Jesus faces three temptations. Just like Israel.

Like Israel, he is first confronted with hunger. He is tempted, as Israel was, to grumble against God (see Exodus 16:1-13).

Next, Satan dares Jesus to put God to the test, to demand that God “prove” His promise to care for Him. Israel underwent the same temptation when the people started fighting with Moses at Massah (see Exodus 17:1-6; Numbers 20:2-13; Psalm 95:79).

Last, Jesus is tempted to worship a false god, which Israel actually did in creating the idol of the golden calf (see Exodus 32).

Jesus answers each temptation with a quote from the Old Testament. But not just any quote. Each time he quotes Moses. And He doesn’t quote Moses randomly.

Each of the quotes is taken from the Book of Deuteronomy – from the precise part of the book where Moses is explaining the lessons Israel was supposed to learn from its years in the desert (compare Matthew 4:4 and Deuteronomy 8:3; Matthew 4:7 and Deuteronomy 6:16; and Matthew 4:10 and Deuteronomy 6:12-15).

C. Blessings of the Kingdom

Jesus, then, is the son of David and the son of God, the Messiah long anticipated by the faithful of Israel.

He comes to His people as a liberator and savior – like the first liberator and savior of Israel, Moses.

Like Moses, Jesus fasts for 40 days and nights alone in the wilderness (see Matthew 4:2;Exodus 34:28).

Like Moses, He ends His fast by climbing a “mount” to give the people the law of God, delivering what we call the “Sermon on the Mount” (see Matthew 5-7; Deuteronomy 5:1-21;Exodus 24:12-18).

The Law given by Moses at Mount Sinai was a Law by which the people were to live in the “promised land.” The new law that Jesus gives in His Sermon on the Mount is the law for the new promised land, “the kingdom of heaven” (see Matthew 5:3,10).

Jesus insists that His new law doesn’t abolish the old Law of Moses or the teachings of the prophets. Instead, He says, He has come “to fulfill” the Law and the prophets (see Matthew 5:17).

Jesus makes the Law of Moses a law for all mankind, a law for governing the human heart, a law for a Kingdom of God that’s bigger than any one nation, a Kingdom that will stretch to the ends of the earth.

The kingdom teaching of Jesus is a “family law” really – a law given by a Father for His children.

The dominant theme in Jesus’ great sermon is the Kingdom. But the Kingdom He envisions is far more than a political institution. The Kingdom of God is the Family of God.

That’s why in the middle of this sermon, He teaches the people to pray to “our Father” and to ask “Your Kingdom come, Your will be done.” (see Matthew 6:9).

The “kingdom of heaven” or the “kingdom of God” was the center of all Jesus’ preaching and miracle working. It was the center of what He sent His Apostles out to teach (see Luke 10:9,11).

Jesus gives us many hints that when He says “kingdom” He means the promised Kingdom of David. For instance, He tells the people in His sermon that they will be “salt of the earth” (see Matthew 5:13).

Jesus is here recalling the reminder of Abijah – that God’s covenant with David was for all time: “Do you not know that the Lord, the God of Israel, has given the kingdom of Israel to David forever, to him and to his sons, by a covenant made in salt?” (2 Chronicles 13:5).

Matthew also says the new people of God are to be “the light of the world” and a “city set on a mountain” (see Matthew 5:14).

He is evoking here the prophecies of Isaiah about the restored kingdom, which was to be a “light to the nations” (see Isaiah 42:6; 49:6).

The spiritual capital of the city, Jerusalem (Zion), the city of David and of the Temple, set on the holy mountain, was to become the seat of wisdom for all nations (see Isaiah 2:2-3;11:9).

Jesus’ preaching of the kingdom is accompanied by miraculous healings – again showing Him to be the expected Messiah.

He makes the deaf hear and the mute speak (compare Isaiah 35:4-5; Jeremiah 31:7-9;Mark 7:31-37). He gives eyesight to blind – who call out to Him: “Jesus, son of David, have pity on me” (see Mark 11:47,49).

D. The Good Shepherd

As David was a shepherd, and as the prophets foretold, Jesus the Messiah came as a good shepherd to save the lost sheep of the house of Israel (see John 10:11; Hebrews 13:20; Matthew 10:6; 15:24; see also Ezekiel 34:23; 37:24).

We see this most clearly in His feeding of the 5,000 (see Mark 6:34-44). The story begins with Jesus pitying the crowd “for they were like sheep without a shepherd” (see Mark 6:34).

Mark wants us to see Jesus as the good shepherd promised by Ezekiel and others.

But as we see past prophecies fulfilled in His miraculous feedings, the Gospel also wants us to look ahead – to the ongoing miracle of the Good Shepherd’s care for His flock in the Eucharist.

Notice the precise actions of Jesus when He feeds the multitudes: He takes the bread; He blesses it; He breaks it; and He gives it.

Now flip ahead to the accounts of the Last Supper. What do we see Jesus doing? He He takes the bread: He blesses it; He breaks it; and He gives it (Compare Mark 6:41 and14:22; Matthew 14:19 and 26:26; Luke 9:16 and 22:19. See also 1 Corinthians 11:23,26).

The Good Shepherd not only seeks out His lost sheep, but He promises to feed and nourish them, to give them their daily bread.

E. The Keys to the Kingdom

As Solomon appointed 12 officers to rule his kingdom (see 1 Kings 4:7), Jesus appoints His 12 Apostles to positions of leadership in His kingdom (see Matthew 19:28).

He appoints, one, Simon, to a special post, changing his name to Peter. Peter is from the Greek Petros, which means “rock.” Jesus tells him, “On this rock I will build my Church” (see Matthew 16:18).

This may be a reference to Solomon, who built the Temple, the house of God, on a large foundation stone (see Isaiah 28:16).

Earlier, Jesus had made another reference to Solomon and the rock – saying that people who live by His new law are like “a wise man who built his house on rock.” Solomon was known for his wisdom (see 1 Kings 3:10-12) and built the Temple on a rock (see 1 Kings 5:17; 7:10).

My Church is the name that Jesus gives to the Kingdom He has come to announce.

And Jesus gives Peter supreme authority in His Kingdom, His Church. He gives Peter the “keys to the kingdom of heaven” and the powers to “bind and loose.”

The only other place in Scripture where such “keys” are mentioned is in a passage about the Davidic kingdom found in a prophecy from Isaiah (see Isaiah 22:15-24).

There, Isaiah prophesies God’s transfer of “the key of the House of David” from a corrupt “master of the palace” named Shebna to a righteous servant, Eliakin. Of Eliakin, the prophet says:

He shall be a father to the inhabitants of Jerusalem, and to the House of Judah. I will place the key of the House of David on his shoulder – when he opens, no one shall shut; when he shuts, no one shall open.

This sounds a lot like what Jesus says to Peter:

I will give you the keys to the kingdom of heaven. Whatever you bind on earth shall be bound in heaven and whatever you loose on earth shall be loosed in heaven.

In the Davidic Kingdom, the king appointed, in effect, a prime minister to handle the day-to-day affairs of the Kingdom. He was called the royal “vizier” or “major-domo,” the “superintendent” or “master of the palace.” He is considered, as Isaiah said, to be “a father to the inhabitants” of the Kingdom (see 1 Kings 4:1-6; 16:9; 18:3; 2 Kings 15:5; 18:18,37;19:2; Isaiah 22:22).

Jesus appoints Peter to be “prime minister” of the restored Kingdom of David, the Kingdom of Heaven that Jesus proclaimed, the Church He called His own.

The “keys” are a symbol of the King’s power, authority, and control (see also Revelation 22:16; 3:7; 1:8).

Jesus’ reference to “binding” and “loosing” alludes to the authority of rabbis in Jesus’ time. The rabbis had the power to make “binding” and “loosing” decisions about the interpretation and enforcement of the Law – they could declare what is permitted and what is not permitted according to the Law.

As prime minister of the Kingdom, rock of the Church, Peter is, in effect, the chief rabbi, with ultimate teaching authority.

IV. New Exodus in Jerusalem

A. With Moses and Elijah

Peter, along with James and John, are chosen to see Jesus “transfigured” in glory on a mountaintop.

The Transfiguration again evokes memories from earlier in salvation history. On the mountaintop, Jesus speaks with Moses and the prophet Elijah. It is a very visual reminder of what Jesus said in the Sermon on the Mount – that He had come to fulfill the Law (of Moses) and the prophets.

What were the three talking about on the mountain? “His exodus that He was going to accomplish in Jerusalem” (see Luke 9:31).

The Greek word “exodus” means “departure.” But in this scene they are talking about more than some generic departure. The Gospel is deliberately referring us back to the exodus of the Israelites out of Egypt.

The prophets had foretold the raising of a “righteous shoot” or son of David, who would lead a new exodus that would gather all the scattered children of Israel into a new kingdom administered by God’s appointed shepherds.

As the first exodus led to the making of a covenant between God and Israel at Sinai, the new exodus, Jeremiah prophesied, would result in a “new covenant” (see Jeremiah 23:3-8;31:31-34).

What will happen to Jesus in Jerusalem – His Passion, death and Resurrection – will be that new exodus the prophets foresaw.

As the first exodus liberated Israel, the new exodus will liberate every race and people. As the first exodus freed Israel from bondage to Pharaoh, the new exodus will free all mankind from slavery to sin and death.

B. Making a King’s Entrance

To begin the accomplishment of this new exodus, Jesus enters Jerusalem in a scene reminiscent of Solomon’s crowning as King (see 1 Kings 1).

Jesus is proclaimed “son of David” (see Matthew 21:9,15) like Solomon (see Proverbs 1:1). He rides a colt into town (see Matthew 21:7) as Solomon rode King David’s mule (see 1 Kings 1:38, 44).

As Solomon is declared king by the crowd in a tumult of rejoicing (see 1 Kings 1:39-40), the crowd greets Jesus with an Old Testament gesture of homage to a king – spreading their cloaks on the road before Him (see Matthew 21:8; 2 Kings 9:13).

C. Passover – Old and New

The night before the Israelites’ exodus from Egypt, they ate a symbolic, ceremonial meal. It was more than a meal, it was to be a memorial – a ritual remembrance of that night for all time.

We’re going to review here some material we covered in Lesson Four (see “The Passover and ‘Our Paschal Lamb'”). But now we’re in the position to see how Jesus, in celebrating His last Passover meal with His Apostles, revealed the full meaning of the Passover.

The Passover recalls the night when God destroyed all the first-borns of Egypt in order to rescue His “first-born son,” Israel (see Exodus 4:22).

On that first Passover night, all Israelite families were ordered to sacrifice an unblemished lamb (see Exodus 12:5) and paint the lamb’s blood with a hyssop branch (see Exodus 12:22) on their door posts (see Exodus 12:7). Then they were to eat the lamb’s “roasted flesh” with unleavened bread (see Exodus 12:8).

When the Lord came that evening for the first-born of the Egyptians, He “passed over” every house with lamb’s blood painted on the door posts (see Exodus 12:12-13,23).

The Israelites were instructed to remember this night forever, “as a perpetual ordinance for yourselves and your descendants” (see Exodus 12:24).

Each year, they would relive the night, as Moses had ordered, by reading the Scriptural account of the first Passover and eating the unblemished lamb with unleavened bread.

The Passover marked their birth as a people of God in the covenant He made with them at Sinai.

That covenant was ratified by the blood of animals offered in sacrifice. Sprinkling them with the blood, Moses said: “This is the blood of the covenant which the Lord has made with you” (see Exodus 24:8).

Jesus had all this background in mind at His Last Supper, which was eaten as a Passover meal. It was celebrated on the night before His “exodus.”

Jesus tells the Apostles that the bread is His body and that the wine is “My blood of the covenant” (see Mark 14:24).

Jesus is making a direct quotation of Moses’ words at Sinai (see Exodus 24:8). In Luke’s account of the Last Supper, the cup is even called “the new covenantin My blood” (seeLuke 22:20).

In explaining the Eucharist, Jesus compared it implicitly with the Passover celebration – saying that people must “eat My flesh,” as the Israelites had to eat the roasted flesh of the Lamb (see John 6:53-58).

In telling His Apostles to “do this in memory of Me” (see Luke 22:19), Jesus was instituting the Eucharist as a “memorial” of a new “passing over” and a new covenant.

We who believe in Jesus are to remember our salvation in a ritual meal – just as the Israelites commemorated their salvation from Egypt.

D. Our Paschal Lamb

The actual “passover” of Jesus takes place in His Passion, death and Resurrection.

Here, we see Jesus identified as both the Passover lamb and the priest who offers the lamb in sacrifice.

Early on, John the Baptist had identified Jesus by the curious label, “the Lamb of God” (seeJohn 1:29).

When Christ is condemned, the Gospel tells us, it was the “preparation day for Passover, and it was about noon.” Why this detail? Because that was the precise moment when Israel’s priests slaughtered the lambs for the Passover meal (see John 19:14).

Later, the mocking soldiers give Jesus a sponge soaked in wine. They raise it to Him on a “hyssop branch.” That’s the same kind of branch the Israelites are instructed to use to daub their door posts with the blood of the Passover lamb (see John 19:29; Exodus 12:22).

And why don’t the soldiers break Jesus’ legs (see John 19:33,36)? John explains that with a quote from Exodus, telling us that it was because the legs of the Passover lambs weren’t to be broken (see Exodus 12:46; Numbers 9:12; Psalm 34:21).

Jesus also is reported to have been wearing a tunic that was “seamless, woven in one piece from the top down” (see John 19:23). This sounds a lot like the special garment worn by Israel’s high priest which was not to be torn (see Leviticus 16:4; 21:10). Note that the soldiers say, “Let’s not tear it” (see John 19:24).

These subtle details are put there to show us that what’s happening on the Cross is a new Passover.

In the first Passover, Israel was spared by the blood of an unblemished sacrificial lamb painted on their door posts. The lamb died instead of the first-born, was sacrificed so that the people could live (see Exodus 12:1-23,27).

It is the same with the Lord’s Passover. The Lamb of God dies so that the people of God might live, saved from their sins by “the blood of the Lamb” shed on the Cross (seeRevelation 7:14; 12:11; 5:12).

“Our paschal lamb, Christ, has been sacrificed,” St. Paul says (see 1 Corinthians 5:7). On the Cross, St. Peter tells us, Jesus was “a spotless unblemished Lamb.” By His “Precious Blood” we are “ransomed” from captivity to sin and death (see 1 Peter 1:18-19).

E. Death of the Beloved Son

More than that, even, what’s happening on the Cross is the fulfillment of the oath that God swore to Abraham back on the Mount of Moriah.

Here we want to recall what we said in Lesson III (see “Binding Isaac”).

On the Cross, Jesus is “reenacting” the story of Abraham’s sacrifice of His beloved son Isaac (see Genesis 22).

Calvary, where Jesus was crucified, is one of the hills of Moriah, the mountain range where the drama of Abraham and Isaac took place.

Recall the repetition of the words “father” and “son” in the Abraham and Isaac story, how Isaac is repeatedly referred to as Abraham’s only and beloved son (see Genesis22:2,12,16).

Jesus, too, is called a “beloved Son” at two crucial points in His life – in His Baptism and Transfiguration (see Matthew 3:17; 17:5).

As Isaac carried the wood for his own sacrifice, and submitted to being bound to the wood, so too Jesus carried His cross and let men bind Him to it.

Abraham had assured his son before binding him on the altar: “God himself will provide the lamb for the holocaust [sacrificial burnt offering]” (see Genesis 22:8).

And indeed God did – centuries later on the Cross at Calvary. There, God accepted the sacrificial death of His only beloved Son.

Abraham received his son back from certain death “on the third day” (see Genesis 22:4). And on the third day, God the Father received His Son back from the dead (see 1 Corinthians 15:4).

In testing Abraham’s faith, God had been showing us the Cross in advance, had been revealing the mystery of His own Fatherly love, of His faithfulness to His covenant promises.

God twice praised Abraham’s faithfulness – “You did not withhold from me your own beloved son” (see Genesis 22:12,15).

When Paul talks about the Crucifixion, he uses the same exact Greek words to describe God’s faithfulness – “He who did not spare His own Son but handed Him over for us all” (see Romans 8:32).

On account of Abraham’s faith, God swore a covenant oath – that Abraham’s children would be “as countless as the stars of the sky” and that through them God’s blessings would flow upon “all the nations of the earth” (see Genesis 22:15-18).

As we have said, this is the covenant that God was honoring at every turn in salvation history – in freeing the descendants of Abraham from Egypt (see Exodus 2:24); in establishing David’s kingdom as an everlasting dynasty (see 2 Samuel 7:8,10,11).

And on the Cross, that promise to Abraham is finally fulfilled. God, in faithfulness to His covenant promise to Abraham, in offering His only begotten Son, made it possible for all peoples to be made “children of Abraham” and heirs of the promised blessings.

As Paul said, the Beloved Son gave His life so that “the blessings of Abraham might be extended to the Gentiles” – that is, to all the peoples of the world, to all those who aren’t children of Abraham by birth (see Galatians 3:14).

By faith in the Gospel, by believing that Jesus is the Messiah, the son of David and the son of Abraham, all men and women are made “Abraham’s descendants, heirs according to the promise” made by God to Abraham back on Moriah (see Galatians 3:29).

V. The End of His Story

A. Beginning with Moses

How do we know all this? How can we be sure that this is the “right interpretation” of what was really happening on the Cross?

Because the Church, building on the testimony of the Apostles, has told us so. How did the Apostles know?

Because Jesus taught them how to find Him in the Scriptures.

On the third day, when He rose from the dead, what was the first thing He did? According to Luke’s Gospel, He appeared to some deeply saddened disciples making their way to Emmaus.

As He walked, He explained the Scriptures to them. “Beginning with Moses and all the prophets, He interpreted to them what referred to Him in all the Scriptures” (see Luke 24:27).

When He was done interpreting the Scriptures to them, He celebrated the Eucharist. Notice the same pattern we observed in the feeding of the multitudes and at the Last Supper. At Emmaus, “He took bread, said the blessing, broke it and gave it to them” (see Luke 24:30).

Later that first Easter night, He appeared to the Apostles. Again, He “opened their minds to understand the Scriptures” (see Luke 24:45).

By Scriptures, of course, Luke means the books of what we call the Old Testament. There were no New Testament writings just yet!

But Jesus was establishing something very important – that what He said and did, the meaning of His life, death and Resurrection, can’t be understood apart from what was written beforehand in the Old Testament.

He told them that God had foretold His coming in every part of the Old Testament, and explained to them “everything written about Me in the Law of Moses and in the prophets and in the Psalms” (see Luke 24:44).

Jesus taught His chosen Apostles how to interpret the Scriptures. And as He promised, He sent them “the Spirit of truth” to guide them “to all truth” (see John 16:13).

What they learned and continued to have revealed to them “in the breaking of the bread” is inscribed on every page of the New Testament and in the Liturgy of the Church.

Indeed, there is not a page of the New Testament that’s not infused with Old Testament quotations or allusions. Even relatively minor Epistles, like that of Jude, contain lessons drawn from the Old Testament.

Listen for the echoes of salvation history as you read the rest of the New Testament.

You will hear the Apostles doing just what Jesus taught them to do – interpreting the Old Testament, explaining how all the great words and events of the past pointed to Jesus, the Messiah, the Word of God come in the flesh (see Acts 8:26-39; John 1:14).

In the Acts of the Apostles, be sure to read the great missionary speeches of Peter (seeActs 2:14-36; 3:12-26; 11:34-43); Paul (see Acts 13:16-41) and Steven (see Acts 7:1-51).

You will hear all the great stories we have looked at in this course – about God’s promises to Abraham, about Moses and the Exodus, the forty years in the desert, and more. More than any other figure, you will hear about David.

B. Kingdom of the Spirit

At the center of the Jesus’ post-Resurrection teaching about the Old Testament was David and “the kingdom of God” (see Acts 1:3).

In the Church, God has “restore[d] the kingdom to Israel” (see Acts 1:6).

Jesus’ Ascension to heaven is described as a royal enthronement – He is taken up to heaven to be seated at the right hand of God for all eternity (see Acts 2:22-36).

Seated on the throne of David, Jesus rules His Kingdom (see Acts 13:22-37). More than a heavenly king, Christ is “a great priest over the house of God” (see Hebrews 10:11).

The Davidic Messiah, we recall, was expected to be “a priest forever” (see Psalm 110:4). And now Jesus is enthroned in the temple and sanctuary of heaven – “a high priest who has taken His seat at the right hand of the throne of the Majesty in heaven” (see Hebrews 8:1; also Hebrews 7).

Jesus reigns now as King and High Priest over a kingdom that is both on earth and in heaven – a kingdom that is both temporal and historical and spiritual and eternal. It is a kingdom that was begun among the children of Israel, but now is to extend to the ends of the earth.

We see this already in the Acts of the Apostles. The progress of Acts shows the Church extending from Jerusalem (Acts 1-7), north to restore the former Northern Kingdom (Acts 8), and from there fanning out to all the nations beyond Israel (see Acts 10-28).

As you read Acts, notice that “the Kingdom of God” is a constant theme of the Apostles’ preaching (see Acts 8:12; 14:22; 19:8; 20:25; 28:31).

This Kingdom is the Church. And the Church is the destiny of the human family. In sending His Spirit down upon Mary and the Apostles at the Pentecost (see Acts 1:14; Acts 2), God announces the crowning of all His mighty works of salvation history.

The Jewish feast of Pentecost called all devout Jews to Jerusalem to celebrate their birth as God’s chosen people, in the covenant Law given to Moses at Sinai (see Leviticus 23:15-21; Deuteronomy 16:9-11).

The Spirit given to the Church at Pentecost seals the new law and new covenant brought by Jesus – written not on stone tablets but on the hearts of believers, as the prophets promised (see Jeremiah 31:31-34; 2 Corinthians 3:2-8; Romans 8:2).

In the beginning, the Spirit came as a “mighty wind” sweeping over the face of the earth (see Genesis 1:2). And in the new creation of Pentecost, the Spirit again comes as “a strong, driving wind” (see Acts 2:2) to renew the face of the earth.

God fashioned Adam, the first man, out of dust and filled him with His Spirit (see Genesis 2:7).

Jesus is “the New Adam” (see Romans 5:12-14,17-19).

Jesus underwent a temptation by the Devil, just as Adam did. He was tempted a final time, in a garden (see Luke 22:39-46), in “the time for the power of darkness,” that is, the time for the Devil’s last stand (see Luke 22:53).

The first Adam, by his disobedience, brought sin and division and death into the world.

By His obedience to God, by willingly emptying himself to come among us as a man and to offer himself in sacrifice on the Cross, Jesus restored our relationship with God (seePhilippians 2:6-11).

We see this on the Cross. What does Jesus say to the good thief? “Amen, I say to you, today you will be with Me in Paradise” (see Luke 23:42).

Paradise, as we learn later in the New Testament (see Revelation 2:7), is the “Garden of God,” the place where salvation history begins and ends – with the human family once more worthy to eat of “the tree of life” (see Revelation 22:2,14,19).

“For just as in Adam all die, so too in Christ shall all be brought to life,” Paul said (see 1 Corinthians 15:22).

As Adam was made a living being by the Spirit-breath of God, the New Adam become a life-giving Spirit (see 1 Corinthians 15:45,47).

He breathed His own life and power into the Apostles after the Resurrection (see John 20:22-23). And beginning at Pentecost, like a river of living water, for all ages He will pour out His Spirit on His body, the Church (see John 7:37-39).

C. Sacraments of Childhood

The Apostles in turn pour out that Spirit upon the world – through the divine ministry of the sacraments.

The sacraments, as the Apostles explained them, continued the mighty works of God in salvation history – localizing them, making them personal, ensuring that all people would be joined to the saving work of Jesus until the end of time.

The sacraments – like everything in the New Covenant – were concealed in the Old and revealed in the new.

Baptism fulfills the covenant God made with Noah. No longer does water destroy the sinful. Now it saves the sinner, destroys the sin (see 1 Peter 3:20-21). But whereas the flood and the ark saved only eight people, in the saving waters of Baptism, in the ark of the Church, all humankind may find salvation.

The waters of Baptism are also likened to the miracle of the parted waters of the Red Sea. When Moses led the people through the waters of the Red Sea, fed them with spiritual food and drink, it was to show us an “example” of our life in the Church.

We will be saved in the waters of Baptism, guided by the Spirit, nourished by the Eucharist in the wilderness of the world (see 1 Corinthians 10).

Receiving the Spirit in Baptism, each man and woman is made a “new creation” (see 2 Corinthians 5:17; Galatians 6:15). According to St. James: “He willed to give us birth by the word of truth that we may be a kind of first fruits of His creatures” (see James 1:18)

This new birth is celebrated throughout the New Testament: “See what love the Father has bestowed on us that we may be called the children of God” (see 1 John 3:1).

This is why the Apostles, like Paul, called themselves spiritual “fathers” (see Philemon 10) and referred to their new converts as “children” (see 1 Thessalonians 2:11) and even “newborn infants” (see 1 Peter 2:2).

Remember, this was the purpose of salvation history in the beginning, the meaning and trajectory of every covenant – to make us children of God. This purpose is fulfilled in Jesus and the Church. In the Church, all are made part of what Paul calls “the family of faith” (see Galatians 6:10).

D. Completing the Word of God

In Jesus, we see the full disclosure of God’s “eternal purpose,” His plan from “before the foundation of the world” – to make all men and women His children by divine “adoption” (see Ephesians 3:11; 1:4-5)

Each of the Baptized has been given a “share in the divine nature” (see 2 Peter 1:4). Each has received “a Spirit of adoption,” making them “Children of God, and if children, then heirs of God” (see Romans 7:15-16) – heirs to the blessings promised at the dawn of salvation history.

Drinking of the one Spirit in the Eucharist (see 1 Corinthians 10:4), believers in the Church are the firstfruits of a new, worldwide family of God – fashioned from out of every nation under heaven, with no distinctions of wealth or language or race, a people born of the Spirit.

The Church, the restored Kingdom, “brings to completion…the Word of God, the mystery hidden from ages and generations past” (see Colossians 1:26).

In the Kingdom, in the Church, the Gentiles, the non-Jews, are “no longer strangers” but are made now “fellow citizens with the holy ones and members of the household of God” (see Ephesians 2:19: 3:5-6).

Much of the drama of Acts, the tension of Romans and Galatians, revolves around the growth and meaning of this Kingdom, how God’s saving purpose was to include the non-Jewish peoples, how the Gospel is to be preached “to the Gentiles that they may be saved” (see 1 Thessalonians 2:16).

And throughout the New Testament we see the Church growing as a visible institution:

- under the leadership of Peter, teaching and interpreting the Scriptures with final and ultimate authority, guided by the Holy Spirit (see Acts 15:24-29);

- writing inspired letters and handing on oral traditions (see 2 Thessalonians 2:15);

- Baptizing and celebrating the Eucharist and other sacraments (see Acts 10:44-48; 2:42);

- creating permanent institutions – priests, bishops and deacons – to carry on the work into the future (see Titus 1:5-9; 1 Timothy 3:1-9; 4:14; 5:17-23).

E. Revealing the End

The New Testament promises that the Kingdom now visible on earth will be consummated in the “heavenly kingdom” (see 2 Timothy 4:18).

And we see a glimpse of that heavenly kingdom in the Bible’s last book, the Book of Revelation.

The Bible began with the story of the creation of the world. It ends with the passing away of heaven and earth and the coming down of “a new heaven and a new earth” (seeRevelation 21:1).

In Revelation, the Apostle John is “caught up in the Spirit on the Lord’s Day” (seeRevelation 1:10) – that is, on a Sunday, possibly while celebrating the Eucharist.

What is revealed to him is the destiny of history, the “goal” or final end of God’s saving plan.

Jesus is unveiled as “the lion of the tribe of Judah, the root of David” (see Revelation 5:5;3:7; 22:16) – in other words the Son of David.

He is “a male child destined to rule all the nations with an iron rod” (see Revelation 12:5), born of a Queen Mother – “clothed with the sun, with the moon under her feet, and on her head a crown of twelve stars” (see Revelation 12:1).

He is revealed as “the Lamb that was slain,” now enthroned in heaven (see Revelation 5:6-14). He is clothed as a high priest and king (see Revelation 1:13) and He is called “the Word of God” (see Revelation 19:13) and “King of Kings and Lord of Lord” (see Revelation 19:16; 11:15).

Jesus is seen summoning people to worship, to enter into His kingdom, to eat with Him, to be enthroned with Him in heaven (see Revelation 3:20-21).

The Church is revealed as “a kingdom, priests for His God and Father” (see Revelation 1:6).

Recall that this was God’s purpose in bringing the Israelites out of Egypt and making them a nation (see Exodus 19:6). The Kingdom of the Churc h, born of the new exodus of Christ, now fulfills God’s purpose – to make a holy family of priestly people (see 1 Peter 2:9).

The Church is founded on “the twelve apostles of the Lamb” and open to the “twelve tribes of the Israelites” (see Revelation 21:12,14). It is made up of both Jews and Gentiles, as John sees it. There are 144,000 “marked from every tribe of the Israelites” plus “a great multitude, which no one could count, from every nation, race, people and tongue” (seeRevelation 7:7,9).

All are gathered before a great throne and the Lamb, and heaven is filled with the sounds and actions of worship. Revelation, in fact, is a picture of the eternal liturgy of heaven, a liturgy that very much resembles the Mass the Church still celebrates on earth.

Through all the visions John records, there are scenes of tribulation and warfare, as the Church struggles against Satan, the great ancient serpent “who deceived the whole world” at the beginning of salvation history (see Revelation 12:9).

The first creation ended with the frustration of God’s plan in the sin of Adam and Eve. The Bible ends with images of triumph and victory – “a new heaven and a new earth” (seeRevelation 21:1).

All the Church is singing a great “alleluia” before the throne of God, joining in celebration of “the wedding feast of the Lamb” (see Revelation 19:6,7,9).

The Groom of the feast is the Lamb, Christ. The Bride is the Church – described as a “holy city, a new Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God, prepared as a bride adorned for her husband” (see Revelation 21:2).

The Church, throughout the New Testament is referred to in female terms – as the “elect Lady” (see 2 John 1), as the bride made “one flesh” with Christ (see Ephesians 5:2), and finally as the “mother” of every Christian born in baptism (see Galatians 4:26).

In drawing these comparisons, Paul in particular, always pointed his readers back to the story of Adam and Eve. The Church is “one body” with Christ in the same way that Adam and Eve – and every married couple – are united as “one flesh” in marriage (see Genesis 2:24; Ephesians 5:30-31).

Remember that Christ is presented to us in the New Testament as a “New Adam.” The Church, His Bride, is the New Eve.

In the garden in the beginning, with the “marriage” of Adam and Eve, God was drawing for us an image of what things would look like in the end.

He was showing us that the relationship He desires with the human race is full communion, intimate love. The only human relationship that can compare is that of the union of man and woman in the marriage covenant.

In fact, throughout salvation history, God compared His Old Covenant to the marriage covenant (see Hosea 2:16-24; Jeremiah 2:2; Isaiah 54:4-8). This explains why Christ described Himself as a “bridegroom” in the Gospels and performed His first miracle at a wedding (see John 2; 3:29; Mark 2:19; Matthew 22:1-14; 25:1-13).

The New Covenant fulfills God’s marital vows to His people. He has become “one body” with them in the Church. This covenant is renewed in each Eucharist, as we are joined intimately to His Body.

As He promised through His prophets (see Ezekiel 27:26-27), God has made His dwelling with the human race: “He will dwell with them and they will be His people and God himself will always be with them” (see Revelation 21:3).

This is the reality we live in now, according to the Bible’s last book.

We are heirs to the victory won by Christ – a victory foreseen by God since before the foundation of the world.

We are the spiritual children, born of the marriage of the Lamb and the Church, having received the divine gift of “life-giving water” in Baptism, having heard God say to each of us: “I shall be his God and he will be My son” (see Revelation 21:7).

By His power, we have been given the “right to eat from the Tree of Life that is in the garden of God” (see Revelation 2:7), the tree spurned by Adam and Eve.

We live in joyful hope waiting for the coming of the Lord again in glory, a coming we anticipate in every celebration of the Eucharist (see 1 Corinthians 10:26).

This is the story of the Bible. And the Bible is now a book, an oracle of God, that we can say we have read, with understanding, from cover to cover.

VI. Study Questions

- Explain the four Old Testament references in the first line of the New Testament (seeMatthew 1:1). Why do we say that this line could stand as a summary of the entire Gospel?

- What does Mary mean when she says the Christ Child fulfills God’s “promises to our fathers, to Abraham and to his descendants forever” (see Luke 1:55).

- How does the New Testament present Jesus as the promised Davidic Messiah in (a) His birth and early years; (b) His Baptism; and (c) His public ministry? Provide examples and quotations from Scripture.

- How does the New Testament present Jesus as a new Moses in (a) His birth and early years; and (b) in His temptation in the wilderness?

- How is Jesus’ death and resurrection a new exodus and a new passover? In what way is the Eucharist a memorial of this new passover and exodus?

- Explain the similarities between Abraham’s “sacrifice” of Isaac and the Crucifixion of Jesus. How does the event of the Cross fulfill God’s promise to Abraham?

- When and how did Jesus teach the Apostles how to interpret the Old Testament Scriptures?

- How does the New Testament present the Church as the restored Kingdom of David and a worldwide family of God?