Lesson Goals

- To read Genesis 12-50 with understanding.

- To understand God’s covenant with Abraham and to see how that covenant is fulfilled in the New Covenant of Jesus Christ.

- To appreciate key figures and elements in the Abraham story – Melchizedek, circumcision, the sacrifice of Isaac – as they are interpreted in the Church’s tradition.

Lesson Outline

I. Review and Overview

Let’s start this lesson with some review: We’re studying salvation history – the story that the Bible tells – by studying the covenants, which form the “backbone” or the “skeletal structure” of the Bible.

In the ancient world, covenants established family relationships. The covenants God makes in the Bible do the same thing. By His covenants, God establishes a family relationship with His creatures, the human people made in His image and likeness. By His covenants, He was – and still is – fathering a family. Through the covenants of the Bible, He bestows His blessing – a share in His divine grace and life – upon His people. By this blessing, He makes us more than simple creatures. He makes us true divine heirs and offspring – sons and daughters.

We’re studying this history to understand better and to live better the New Covenant, which He gave to us in the person of Jesus Christ, and which we entered into through Baptism. And all of the covenants we read about in the Old Testament history of the Bible are intended to foreshadow, to anticipate and point to, the New Covenant.

Picking up the story in the Bible: As a result of the original sin of Adam and Eve, the family that God desired was fractured and divided. There was now a constant tension between those who doubt God’s promises and seek to glorify their own name, that is, to live outside of God’s family, and those who “call on the name of the Lord,” that is, those who desire to live as His children (see Genesis 4:26).

This tension reaches a head in the Tower of Babel episode we looked at in the last lesson – where the peoples of the world try to “make a name for themselves.” As Adam and Eve sought to live without God, to be “like gods” themselves, now men and women acting together as one people have begun to do the same thing (see Genesis 11).

But in the verses immediately following Babel, we’re introduced to Abram or Abraham. (For simplicity’s sake, we’re going to refer to him as “Abraham” throughout this lesson, even though he’s called ” Abram” until God changes his name in Genesis 17:5).

Abraham is called to reject the ways of those who would exalt themselves and try to make a name for themselves. If he follows God in faith and obedience, God promises to exalt him – to make his name great (see Genesis 12:2).

With Abraham, human history becomes salvation history. Until now, our history was headed to a dead end, toward death, a return to the dust from which man was first fashioned (see Genesis 1:19; Catechism, no. 1079-1080). By his faithfulness, Abraham becomes the father of a new generation of men and women, a generation that lives by faith in the promises of God, as trusting sons and daughters.

Abraham, God promises, will be “the father of a host of nations” (see Genesis 17:5). Through his descendants, he will be the bringer of divine blessing to all the nations of the earth (see Genesis 12:3). What is the blessing that God wants to bestow? The gift of divine sonship. These promises of God, which we focus on in this lesson, are fulfilled in Jesus, who is, as we read in the very first line of the New Testament, “the Son of Abraham” (seeMatthew 1:1).

II. Our Father Abraham

A. The Love Story of God and Humanity

The point of the first three chapters of Genesis is to show us that creation was a deliberate, purposeful act of love by God. The world didn’t just happen. God wanted the world – not because He was lonely, not because there was anything He lacked or needed.

God created the world because God is love (see 1 John 4:16). And love is creative, self-giving and life-giving.

God made the world as a pure gift of His love. He created the world as His home, a sort of cosmic temple in which the heavens are the ceiling and the earth – with all its vast continents, rivers, oceans, mountain ranges and the like – is the floor. The world is made to be a temple where He will dwell with the descendants of the man and woman, the crown jewel, of His creation.

The world is made to be the site where God will live in communion with the people He created. That’s what the seventh day, the Sabbath, means (Genesis 2:1-3).

The seventh day marks the completion of God’s work on His dwelling, and this is the day He makes a covenant with the people He created. As we said in our last lesson, “covenant” is the way that God makes His people into a family. On the seventh day, God made Adam and Eve part of His family.

The covenant of creation, then, is the first sign of God’s intentions for the world and for the human race. It’s true that the word “covenant” isn’t mentioned in the Genesis account. But it’s everywhere between the lines.

Some scholars believe Genesis records a seven-day creation because the root of the Hebrew word for “covenant oath-swearing” – sheba – stems from the word “seven.” To swear an oath means, literally, “to seven oneself” (see Genesis 21:27-32). We can say that God made the world in seven days as an act of cosmic oath-swearing, a “sevening of Himself” to His creation – He created in order to covenant.

Later, God reveals to Moses that the Sabbath is to be observed as “a perpetual covenant” (see Exodus 31:16-17). The Sabbath becomes the day of worship, when God and the people He created in His image rest together in love. (see Exodus 20:8-11; 31:12-17;Deuteronomy 5:15; 12:9; Ezekiel 20:12).

The Catechism calls the creation story the “first step” in “the forging of the covenant of the one God with His people…the first and universal witness to God’s all-powerful love” (no. 288). That’s why Jesus says: “The Sabbath was made for man, not man for the Sabbath” (see Mark 2:27-28).

It’s very important that we understand this covenant of creation.

Because it is the archetype – the source and model – for all the covenants that we will be studying in this course. Every one of the future covenants – with Noah, Abraham, Moses, David and the New Covenant of Jesus – is a remembrance and a renewal of this first covenant with creation.

In other words, in those future covenants, we will find that God is remembering, rededicating and recommiting Himself, so to speak, to this original covenant. This is how the ancient Jews looked at the covenants. We can see that in some of the so-called “intertestamental literature” – Jewish religious books and commentaries written between the close of the Old Testament and the beginning of the New (see Jubilees 36:7; 1 Enoch 69:15-27).

As the covenants of old are described as renewing the covenant of creation, the New Covenant – the final and everlasting covenant – is described as bringing about a new creation.

Jesus, “the firstborn of all creation” becomes the “firstborn from the dead” and the “firstfruits” of a reborn humanity (see Colossians 1:15-20; 1 Corinthians 15:20). Those who enter into that New Covenant through Baptism become “new creations” (see 2 Corinthians 5:17; Galatians 6:15). Finally, the Letter to the Hebrews tells us: “A Sabbath rest still remains for the people of God” (see Hebrews 4:9).

What we’re saying here has been beautifully summed up by Pope Benedict XVI:

” Creation moves toward the Sabbath…The Sabbath is the sign of the covenant between God and man; it sums up the inward essence of the covenant….Creation exists to be a place for the covenant that God wants to make with man. The goal of creation is the covenant, the love story of God and man” (see The Spirit of the Liturgy, pp. 25-27)

Remember that line: The goal, the purpose – the reason that God made the world “in the beginning” – is the covenant, the communion of love that He desires with the human race.

B. Beloved Sons

In the famous biblical canticles of Mary and Zechariah, we’re told that the coming of Jesus fulfills the promises that God swore to Abraham (compare Luke 1:55, 72-73 and Genesis 12:3; 13:15; 22:16-18).

Jesus is the descendant of Abraham in whom the blessings of divine sonship will flow to all the nations of the world. Jesus Himself taught us to see a symbol of His coming in the birth of Isaac: “Abraham your father rejoiced to see My day; he saw it and it was glad.” Of course, Abraham didn’t literally see Jesus’ day. He rejoiced at the birth of His heir, Isaac (see Genesis 17:7). But Jesus is telling us that in Isaac we should see a foreshadowing of His own birth.

Beginning within the Bible and coming to full flower in the writings of Church Fathers like St. Augustine, many have seen deep connections between the life of Isaac and the life of Jesus. Isaac’s birth is a miracle – coming as it does to a 100-year-old man and his barren wife. So Jesus is born by divine conception. As Isaac is circumcised to enter into membership in the chosen people of God, so is Jesus (see Luke 2:21).

There is an even more profound symbolism in the awful test that God gives to Abraham – to offer his only beloved son, Isaac, as a sacrifice. This story has long been interpreted as foreshadowing God’s offering of his only beloved Son on the Cross at Calvary.

First, notice in the story how many times the words “father” and “son” are used (seeGenesis 22). Isaac is described as the only beloved Son of Abraham (see Genesis22:2,12,16). Page ahead to the New Testament and you’ll find God using these same words – “my beloved Son” – to refer to Jesus at two crucial points in His life, in His Baptism and Transfiguration (see Matthew 3:17; 17:5).

This language is not coincidental. It’s the clue to what’s going on in the Abraham story, which is one of the most difficult to understand in the entire Bible. Without this clue, we’re left to draw cruel conclusions: How could God require anybody to sacrifice his only son – or any son, for that matter? What kind of God would demand such a test of loyalty?

But this test, like so many things written in the Old Testament, was written as a “figure,” to teach us a lesson about the loving plan of God (see 1 Corinthians 1:11; Romans 4:23-24). The writers of the New Testament clearly understood that this story was not about a cruel God who asks believers to do horrifying things to serve Him. They knew that in the story of the father Abraham and his son Isaac, God was revealing to us something of the mystery of His own divine fatherhood.

God twice praises Abraham’s faithfulness – “You did not withhold from me your own beloved son” (see Genesis 22:12,15). St. Paul cites the Greek translation of these exact words when He talks about the Crucifixion – “He who did not spare His own Son but handed Him over for us all…” (see Romans 8:32). We can also hear an echo of God’s praise in the famous Scripture from the Gospel of John: “God so loved the world that He gave His only Son…” (see John 3:16).

And there are other, more subtle, parallels, as well: For instance, the mountain where God tells Abraham to perform the sacrifice: Mount Moriah is in the same place that Melchizedek came from – Salem. In fact, Jewish tradition holds that Moriah is the site atop which Solomon built the Lord’s Temple (see 2 Chronicles 3:1). In fact, Jewish tradition also holds that the name “Jerusalem” comes from attaching Abraham’s word of faith – God “will provide” (see Genesis 22:8; Hebrew = yir’eh or jira) to the word Salem.

Calvary, where Jesus was crucified, is one of the hills of Moriah. And as Isaac carried the wood for his own sacrifice, and submitted to being bound to the wood, so too will Jesus carry His cross and let men bind Him to it. Jewish tradition believed that Isaac was between 27 and 35 at the time of this event and that he willingly allowed himself to be bound and offered by Abraham. This would suggest an even further parallel between Isaac and Jesus – both giving themselves up, freely accepting their own death as an offering to God.

Abraham’s words to his servants: “We will worship and then come back to you” (seeGenesis 22:5) can be heard as a promise of resurrection. Why did he say “we,” if he expected that Isaac would be slain? The Letter to the Hebrews explains that it was because Abraham had faith in the resurrection: “He reasoned that God was able to raise even from the dead, and he received Isaac back as a symbol” (see Hebrews 11:17-19). In fact, Isaac is spared, as Jesus will be, “on the third day” (see Genesis 22:4).

C. Signs of Flesh and Spirit

Abraham believed that God would give his only beloved son back to him. And by this faith, he upheld his obligation to the covenant he entered into with God.

God made faith in His promises the condition of His covenant with Abraham. Faith is likewise the condition of those who would enter into the New Covenant made in Jesus.

We see this worked out in the letters of St. Paul, especially in His letters to the Romans and the Galatians. Abraham, Paul says, is “the father of all…who believe” (see Romans 4:11-12). What the Scripture said of Abraham – “faith was credited Abraham as righteousness” – is also the condition required of us. We, too, must trust in God’s promise, “believe in the One who raised Jesus our Lord from the dead” (see Romans 4:9, 23-24).

The blessings that God promised to bestow on the world through the descendants of Abraham come to us through our faith in the Cross and Resurrection of Jesus. The sacrifice of Christ brings to us “the blessing of Abraham” (see Galatians 3:14). These blessings of our father Abraham flow to us in Baptism, which is the sign of the New Covenant, as circumcision was the sign of God’s covenant with Abraham.

God made circumcision to be a sign of His covenant oath to make Abraham’s descendants a royal dynasty: “Thus my covenant shall be in your flesh as an everlasting pact” (seeGenesis 17:1-14). But as St. Paul teaches, this covenant sign in the flesh was meant also to symbolize the spiritual and sacramental sign by which we enter into the New Covenant, the royal family of God.

Already in the prophets, “circumcision of the heart” had become a sign of dedication o f one’s whole being to God (see Deuteronomy 10:16; Jeremiah 4:4; compare Romans 2:25-29; 1 Corinthians 7:18-19). The prophet Jeremiah said that the law of the New Covenant would be written on the heart (see Jeremiah 31:31-34).

And this happens in Baptism, which is the “circumcision of Christ” (see Colossians 2:11) and the true circumcision (see Philippians 3:3). As circumcision was the sign of membership in the people of Abraham, the “new circumcision” – Baptism – is the sign of membership in the Church, the new people of God.

And it is in those baptized in the Church that the promise to Abraham is fulfilled – that “a great multitude, which no one could count, from every nation, race, people and tongue” would find blessing and salvation in the God of Abraham (compare Genesis 15:5 andRevelation 7:9-10).

D. Shem’s Blessing

God promises to bless Abraham. And we know that those blessings come in his descendants, especially in Jesus. But during the course of Genesis, the only actual blessing that Abraham receives is from the mysterious king-priest, Melchizedek (seeGenesis 14:18-20).

We have to do a little background, and even a little math, to understand what that’s all about.

If you notice, God has lots of problems with his “first-born” sons in Genesis – beginning with Adam, who commits the original sin. Adam’s first-born, Cain, in turn becomes a murderer.

In the ancient world, to be first-born son was to be the sole inheritor of all the assets, privileges and powers of the father. To receive his father’s blessing was every son’s goal. In the Bible, this “natural” pattern is given a supernatural spin – not to mention some unexpected twists.

God intended to bestow His blessings on the world through His “first-born,” Adam. But Adam, through his pride and disobedience, failed to live up to the obligations of his birthright. So, God raised up a new first-born, Noah, who proved to be “a good man and blameless in that age” (see Genesis 6:9).

Through the faithfulness of Noah, God renewed his covenant with creation and the human family (see Genesis 9:1-17). But the first-born Noah, like Adam before him, fell into sin (seeGenesis 9:20-22). Still, despite man’s unfaithfulness, God is always faithful to His covenant promises. So He turns to a new first-born, Shem, the righteous first-born of Noah.

Shem receives a cosmic blessing from Noah – “Blessed be the Lord, the God of Shem!” – which marks the first time in Scripture that God is identified with any one human being (seeGenesis 9:26-27). God is designated as “the God of Shem” – a sign of Shem’s great righteousness and stature before God.

However, then Shem disappears. Unlike the other first-borns – Adam, Cain, Noah – we don’t see him fall into disgrace. In fact, we don’t hear anything more about him – except that he has sons and that ten generations later one of his descendants, Terah, gives birth to three sons, the first-born of which is Abraham (see Genesis 11:26-27). It is very curious, though, that we never see Shem – heralded as the most righteous of the men born after the Flood – handing on his blessing to his first-born or to any one of his children.

This is where the math comes in: Add up the numbers given in the account of the descendants of Shem’s line (see Genesis 11:10-26): Abraham is born 290 years after Shem’s first-born, Arpachshad. Now, if Shem is 100 years old when Arpachshad is born, that means that he’s 390 when Abraham is born. And, if Shem lived five hundred years after Arpachshad’s birth, and Abraham lived to be 175 years old (see Genesis 25:7), that means that Shem outlived Abraham by 35 years.

Who cares? Why does it matter? Well, for the ancient rabbis and for centuries of early Christian interpreters, including probably the author of the Letter to Hebrews, it mattered a great deal. It’s also the key to figuring out what’s happening between Abraham and Melchizedek in Genesis 14.

According to a long tradition – Jewish and Christian – the mysterious Melchizedek is actually Shem, the great patriarch, the righteous inheritor of the blessings promised by God after the Flood.

Let’s look at some of the clues in the biblical text. Notice carefully the kingdoms that are represented at the beginning of Genesis 14, especially how they can be traced to the genealogy of the sons of Noah – Ham, Japheth and Shem.

Sodom, Gomorrah, Admah and Zeboiim are all kingdoms descended from Canaan, son of Noah’s wicked son, Ham (see Genesis 10:6, 19). Shinar is another kingdom descended from Ham (see Genesis 10:6, 10). Elam appears descended from Shem (see Genesis 10:22). And the kingdom of Goiim (in Hebrew, literally “the nations”) appears descended from Japheth, father of “the maritime nations” (see Genesis 10:5).

The battle lines drawn up in Genesis 14 are confusing, but here’s what happened: the king of Elam, aligned with three other kingdoms, defeated an alliance of the kings of Sodom, Gomorrah, Admah, Zeboim and Zoar, reducing them to servitude (see Genesis 14:17). Abraham, in turn, defeats the alliance led by the king of Elam, in order to rescue his nephew, Lot, who had been seized as a prisoner of war in the earlier battle.

As a result, the descendent of Shem, Abraham, now ruled over the descendants of Ham and Japheth – just as Noah had prophesied would happen (see Genesis 9:25-27).

Precisely at this moment, Melchizedek appears. And what does he do? He pronounces a blessing over Abraham that sounds a lot like the blessing that Noah pronounced over Shem (see Genesis 14:19-20).

E. First-Born High Priest

What does all this mean?

If Melchizedek, a name which means “king of righteousness” (see Hebrews 7:2), is really Shem, the great son of Noah, then it means that the blessing God gave to Noah and Noah in turn gave to Shem is now being passed on to Abraham. The blessing of the righteous first-born will pass from Abraham on to Isaac (see Genesis 25:5) and to Jacob (seeGenesis 27:27-29).

But with Melchizedek this blessing of the first-born becomes something royal and something priestly. And this becomes something crucial for the plot and meaning of the rest of the Bible.

Melchizedek is a high priest and a king. If he’s also the first-born son of Noah, then his blessing upon Abraham is a sort of “ordination,” a consecration, by which Abraham too becomes, not only a righteous first-born son, but a priest of God Most High.

Already in Genesis, we have seen that Abraham builds altars and calls upon the name of the Lord (see Genesis 12:8; 13:4). But with this blessing, this priestly task becomes a part of his very identity and a part of the legacy and dynasty that God has promised him. We will see Isaac follow in his father’s footsteps (see Genesis 26:25).

And, in our next lesson, when we read of the covenant with Moses, we’ll see that the nation of Israel is conceived as God’s “first-born son” (see Exodus 4:22) and a “kingdom of priests” (see Exodus 19:6).

When we read of the covenant with David, we’ll see that David and his son, Solomon, are considered “first-born” sons (see Psalm 89:6) who are both kings and priests (see 2 Samuel 6:12-19; 1 Kings 3:15; 8:62-63). Interestingly, within the Old Testament, Melchizedek is interpreted as a figure who foreshadows David, who is declared “a priest forever according to the order of Melchizedek” (see Psalm 110:4).

Notice that Melchizedek appears out of nowhere. He has no genealogy and his capital, “Salem” isn’t mentioned before in the book. But Salem, as we see later in the Bible, is a short form of the name Jerusalem, the royal-priestly capital of the chosen people (seePsalm 76:2).

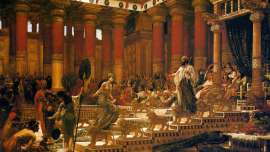

Finally, in the New Covenant, Jesus is seen as first-born, high-priest and king (seeHebrews 1:2-13; 5:5-6). And He too is seen as a priest in the line of Melchizedek (seeHebrews 7). Notice that Melchizedek brings out bread and wine in thanksgiving before he declares a blessing on Abraham. The text associates this action with his being “a priest of God Most high” (see Genesis 14:18).

Jesus, too, brings out bread and wine to symbolize the New Covenant. The Church Fathers, easily saw the action of Melchizedek foreshadowing the Eucharist. And the Church’s Liturgy reflects this tradition in its First Eucharist Prayer, which refers to “the bread and wine offered by your priest Melchizedek (see Catechism, no. 1333).

The brothers and sisters of Jesus in the Church, “the assembly of the firstborn” (seeHebrews 12:23), are also a priestly and royal people (see 1 Peter 2:9; Revelation 1:6).

All of this, in turn, points us back to the Garden, the beginning of human history. It’s very interesting to observe that Adam is placed in the Garden “to cultivate and care for it” (seeGenesis 2:15). Something important gets lost in the translation of those words.

In the original Hebrew text, the words used are ‘abodah and shamar. And they are words associated with priestly service. In fact, the only other places in the Bible where you find those two words used together are in the Book of Numbers, where they are translated as “service,” and “charge,” and used to describe the duties of the Levites, the appointed priests of Israel (see Numbers 3:7-8; 8:26; 18:5-6).

Adam, it appears, is being described as a first-born priest. Commanded to “be fertile and multiply” (see Genesis 1:28), he is, in effect, being made to be the father of a priestly people. This is the destiny of the human race. A destiny that will finally be achieved in Jesus – the “first-born” royal Son and priest (see Hebrews 1:6; 5:5-6).

III. Age of Patriarchs

A. Jacob the Younger

With the story of Abraham we turn a page in salvation history. The remainder of Genesis (chapters 12-50) tells the story of the “patriarchs,” the founding fathers of the chosen people. In Genesis 12-25:18, we’ll read about Abraham and his two sons, Ishmael and Isaac. In Genesis 25:19-36:43, we hear the story of Isaac and his two sons, Esau and Jacob. And the book concludes, in Chapters 37-50, with the story of Jacob’s 12 children, founders of the tribes of Israel, and especially Jacob’s son, Joseph.

Isaac grows up to marry Rebekah. Like his mother Sarah, she’s barren. But Isaac, as his father Abraham had before him, appeals to God to give them children (see Genesis 25:21;15:3). While her twins are fighting in her womb, God tells Rebekah that each will be a nation, but the younger of the two, Jacob, will rule the older, Esau (see Genesis 25:23).

This is another sub-plot in Genesis, closely connected to what we’ve talked about already concerning the “first-born.” Notice that after the failure of His first-born in Eden, God seems to prefer the younger son: Abel’s offering is preferred to Cain’s. Isaac is chosen over Ishmael. Jacob’s youngest son, Joseph, becomes the hero of the later books of Genesis, while Reuben, Jacob’s first-born, fails to defend him against his brothers (see Genesis 37).

Why does God do this? He chooses the young, the weak and the sinful to show that salvation history is governed by His free grace and His love. St. Paul gives us the general principle when he says that God chose Jacob over Esau “in order that God’s elective plan might continue, not by works but by His call…So it depends not upon a person’s will or exertion, but upon God” (see Romans 9:11-13).

Don’t be distracted by the drama and trickery of how Jacob secures Isaac’s blessing. Esau had proven himself unworthy of the blessing, selling his birthright to Jacob for a bowl of stew. As the Scripture says: “Esau cared little for his birthright” (see Genesis 25:29-34).

Jacob’s deception is criticized by the prophets (see Hosea 12:4; Jeremiah 9:3), and he gets his “payback” within the text of Genesis. For instance, he will be tricked by his uncle Laban into marrying not Rachel whom he loves but Laban’s firstborn daughter, Leah (see Genesis 29:25). And later, when his son Joseph is sold into slavery, his other sons will deceive him by soaking Joseph’s coat in goat’s blood. The irony surely isn’t lost on the narrator of Genesis – Jacob’s deception of his father had involved the use of goat skins (compareGenesis 27:15-16; 37:31-33).

But Jacob’s lie serves God’s purposes. God chose Isaac over Esau (see Malachi 3:1;Romans 9:13). Through Jacob, God will extend the blessing he gave to Abraham (seeGenesis 28:3-4). God Himself confirms this in showing Jacob a ladder into the heavens (see Genesis 28:10-15). Later, Jesus will apply this dream to Himself, revealing that in Him heaven and earth touch, the human and the divine meet. He is what Jacob saw as “the gateway to heaven” (see John 1:51; Genesis 28:17).

God changes his name to Israel after a mysterious all-night struggle. The name Israel means “He who contended with God” (see Genesis 35:10; Hosea 12:5).

B. Joseph and Judah

Jacob’s twelve children – born of his two wives, Leah and Rachel – form the twelve tribes of Israel (see Genesis 47:27; Deuteronomy 1:1).

And in the story of Joseph and his brothers, we again see God choosing the youngest to carry out His plan of salvation.

Joseph is a type of Jesus. What happens to him foreshadows not only what will happen to children of Israel, but also the sufferings and the salvation won for us by Jesus.

Joseph is the victim of jealousy and rejection by His brothers, the children of Israel, and is sold for the price of a slave (compare Genesis 37:28 and Matthew 26:14-15). Compare the words of Joseph’s brothers to the words of the evil tenants in the parable of Jesus (seeGenesis 37:20; Matthew 21:38).

Still, both Joseph and Jesus forgive their brothers and save them from death. The Pharaoh tells his Egyptian servants to do whatever Joseph tells them. And Mary will echo these words, telling the servants at the wedding feast to do whatever Jesus tells them to do (compare Genesis 41:55 to John 2:5).

As Joseph explains to his brother, his story shows us that even what men plan as evil, God can use for the purposes of His saving plan (see Genesis 50:19-21).

The Bible’s first book ends with Israel on his deathbed giving his blessing to his children. To one – Judah, he promises a royal dynasty that will be everlasting (see Genesis 49:9-12). He will rule over all peoples of the world – a Scripture that the Church interprets as a promise of Jesus, the Messiah-King. The line of Judah is the line of the kings David and Solomon (see2 Samuel 8:1-14; 1 Kings 4:20-21).

Jesus will come as the royal son of David (see Matthew 1:1-16) and the Lion of Judah (seeRevelation 5:5).

In our next lesson, we’ll see how God fulfills the promise of Abraham, the promise that his grandson, Jacob, repeats when he says to Joseph: “God will be with you and will restore you to the land of your fathers” (see Genesis 48:21).

It’s important to remember, however, that the “land” that we speak of so much in these early covenants “does not belong exclusively to the geography of this world,” as Pope John Paul II has said in his extraordinary homily, Commemoration of Abraham.

When we read the Abraham story and the stories that follow, we need to always be mindful, as the Pope says: “Abraham, the believer who accepts God’s invitation, is someone heading towards a promised land that is not of this world…In the faith of Abraham, almighty God truly made an eternal covenant with the human race, and its definitive fulfillment is Jesus Christ,” Whom by His Cross and Resurrection leads us “into the land of salvation that God, rich in mercy, had promised humanity from the very beginning.”

IV. Study Questions

- What are the three parts of the covenant that God makes with Abraham?

- How, according to the Church’s ancient tradition, is the sacrifice of Isaac similar to the sacrifice of Christ on the Cross?

- Why are the concepts of “first-born son” and “priest” important for understanding the plot and the meaning of the Bible.

For Personal Reflection

The Church’s Liturgy of the Hours has always included the Canticle of Zechariah (see Luke 1:68-79) in its Morning Prayers and the Magnificat (see Luke 1:46-55) in its Evening Prayers. Both prayers see the coming of Jesus as the fulfillment of God’s covenant with Abraham. Pray these biblical prayers of the Church and ask God to help you understand more fully “his promise to our fathers, to Abraham and his descendants forever.”