There are Jewish spirits in Catholic Poland, made from flakes of black ash, sealed in a silent sky with the tears of lost memories. These things Rabbi Byron Sherwin believes.

“In Poland, a Jew is never alone,” he says. “The souls of our ancestors encompass us, welcome us, embrace us.”

He first heard the soft callings of his ancestors in the Polish lullabies his grandmother used to sing. She had come to America from Warsaw in 1912, leaving behind a country where her roots stretched five centuries deep to settle in a mixed ghetto of Jews and Catholics in the Bronx.

From his childhood in that neighborhood where, as he remembers it, “the Italians spoke Yiddish and Jews spoke Italian,” Rabbi Sherwin has grown up in friendship and conversation with both Catholics and the ghosts of Polish Jewry.

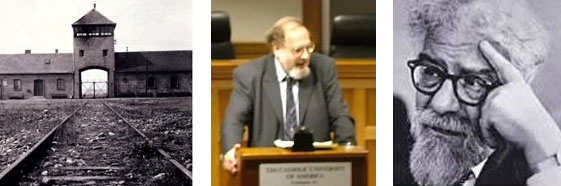

Today, as director of the Joseph Cardinal Bernardin Center for the Study of Eastern European Jewry at Spertus College of Judaica in Chicago, Rabbi Sherwin is a leading voice in that worldwide and historic conversation.

The first rabbi in 400 years to lecture at the Catholic seminary in Bialystok, and the first Jew ever to lecture on Judaism at the University of Warsaw, Rabbi Sherwin can take pride in the Bernardin Center’s efforts to keep Catholic-Jewish dialogue alive during what is widely regarded as a period of provocation and controversy.

The six years that the center has been open have been clouded by a bitter dispute over relocating a convent near Auschwitz, the site of the Nazis’ most notorious death camp and, for many, the ultimate symbol of the Holocaust.

That dispute bore out what Cardinal Bernardin and Spertus College officials had assumed in founding the center — namely, that Poland is the crucial missing link, not only for reconciling the Holocaust memories of Jews and Catholics, but for reclaiming their common history and destiny.

Of The Departed Jews

Poland is, in many ways, the land of the departed Jews.

Where once Jews made up more than 10 percent of Poland’s population, today only a scattering of 10,000-15,000 remain. But the artifacts of a once-thriving Jewish culture—rundown synagogues, crowded graveyards, abandoned concentration camps—still dot the landscape and trouble the Polish imagination, according to Sherwin.

The absence of the Jews, and rumors of the glorious culture they once had in Polania, has opened up an aching hole in the Polish heart.

“The Poles,” he said in an interview, “look back at this Jewish experience, in a way mournfully, as somehow a part of their national heritage and identity that is not accessible to them.”

To help heal that breach, the Bernardin Center has since 1987 worked closely with Poland’s top Catholic leader, Cardinal Joseph Glemp, and Archbishop Henryk Muszyuski, head of a special Church commission on improving dialogue with Judaism. In trying to mold the next generation of Polish Church leaders, the center has focused on training seminarians and university professors in Jewish faith and history.

Perhaps the first official fruits of the center’s efforts can be seen in the Polish bishops’ 1990 pastoral letter on Jews—a stirring condemnation of anti-Semitism and an affirmation of the unbreakable bond between Catholics and Jews—that was mandated to be read in every parish in Poland.

In the years ahead Rabbi Sherwin believes that Poland will emerge as the place where crucial breakthroughs in world Jewish-Christian understanding are made.

“There is a tremendous openness to a real theological dialogue there, as opposed to what we have in America, which is a more social-activist-oriented dialogue,” he said.

While Rabbi Sherwin credits the Catholic side with making “enormous strides” since the Second Vatican Council of the 1960s in rethinking its teachings on Jews and Judaism, he says Jewish leaders have been slow to rethink their prejudices about Christianity.

A ‘Failed’ Messiah

Jewish attitudes historically have been influenced by their experience of anti-Semitism, he explained. Facing hostility and cruelty at the hands of the followers of Jesus, they concluded that He was a betrayer of the Jews, a demonic fraud, a “false Messiah.”

But in the wake of the Church’s repudiation of anti-Semitism, Rabbi Sherwin feels the hour is right for “a new Jewish view of Jesus.” In a May 1992, he advanced this new view in a major address delivered to a conference of Catholic and Jewish scholars in Poland.

Jews, he said, can accept Jesus as kin to what their tradition has labeled “failed messiahs”— social and religious critics who suffered and died in trying to call Jews to change their ways before the coming of the Messiah.

That Jesus was not the Messiah expected by Jews is evidenced by the fact that the world was not finally redeemed from poverty, injustice and war, according to Rabbi Sherwin’s argument.

In accepting Jesus as “a Jewish messiah, but not the Messiah,” Rabbi Sherwin believes Jews can appreciate and study the Rabbi from Galilee as a Jew who continues to have something legitimate, maybe even vital, to say to fellow Jews. Likewise, Sherwin hopes to make clear — to Christians, Jews and the world — that Jesus, the Galilean Jew, continues to hear and bear the special sorrows and burdens of the Jewish people.

A philosopher who has written a dozen books on Jewish culture and religion, and a professor and academic vice president of Spertus, Sherwin sees Poland as “the lost Atlantis of East European Jewish life” — the missing key to Jews’ understanding of their spiritual identity, history and destiny.

In a series of addresses in Poland in recent years, he has unfolded his understanding of the importance of what he calls “the theological heritage of Polish Jews.”

Poland symbolizes for many Jews the death of their people, their utter abandonment by God, he notes. The country is the dark underside of the shining star of the state of Israel, which many Jews herald as a sign of God’s redemption of His chosen people after the horrors of the Holocaust.

At the same time, he argues, Jews have grown increasingly “secularized” since the Holocaust, and many have lost sense of the Jewish people’s special covenant with God and their ethical mission to the world. Instead, for many “Jewish” is only ethnic signifier, or a nationality that finds its expression in the state of Israel.

Sherwin feels that in rejecting Poland as the blood-stained capital of anti-Semitism, Jews — especially those in America — risk closing themselves off from a rich font of spiritual renewal.

Along with long periods of discrimination and humiliation, the history of Polish Jewry includes centuries in which Jewish culture and religion flourished and Catholics and Jews lived peacefully, he stresses.

Hasidism, the most far-reaching Jewish renewal movement, originated in Poland, and Judaism’s greatest spiritual masters since biblical times hail, not from Jerusalem, but from Polish cities such as Lublin, Góra, Kawaria, Kraków and Mackow.

“Eventually, and I think soon, the American Jewish community will, as part of their natural search for roots and identity, start looking to Poland, now that communism has fallen in Eastern Europe,” Sherwin says. “Poles are our spiritual and physical link with the past.”

Hasidic Footprints

In his concern for the spiritual renewal of his people, Rabbi Sherwin is tracking in the footsteps of his mentor, the late Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel.

The last of the great Polish Hasids, born in Warsaw in 1907, Heschel’s warm reception by Popes John XXIII and Paul VI helped build Jewish support for Vatican II’s landmark statement on the Jews in 1965.

Sherwin was Heschel’s last protégé, and he sees his direction of the Bernardin Center’s work in Poland as the “fulfillment of my destiny, if not my training.”

In searching for his own Polish roots, which he can trace back 22 generations, he unearthed a profound spiritual and blood link with Heschel, a link that he interprets as an almost mystical affirmation of his life’s work.

In a 17th-century Jewish graveyard in Krakow he discovered one of his distant ancestors buried, side by side, with one of Heschel’s.

Researching further, he learned that Heschel’s ancestor was the chief rabbi of Kraków and, upon his death, Sherwin’s relative succeeded him. Moreover, the two families intermarried in the 17th century.

His encounter with the Jewish ghosts of Catholic Poland has convinced Rabbi Sherwin that Poland is more than “the lost Atlantis” of East European Jewry. Today, he says, it is also the lost Atlantis of Jewish and Catholic understanding.

There, Sherwin has written, “in the land called the ‘Christ of Nations,’ Jews and Christians — Poles alike, joined in a solidarity both of suffering and of spiritual achievement.”

For him, this legacy of solidarity confirms the Hasids’ mystical belief that every soul bears “holy sparks” that correspond to the holy sparks found in a particular place. Each person must, the Hasids say, travel to their destined place and merge their own personal sparks with the sparks of that place. In the conversation begun by Sherwin and the Bernardin Center is the intimation that the sparks of Jewish-Christian understanding will one day be found in Poland, mingled with flakes of black ash, and the soft calling of shared memories.

Originally published in Our Sunday Visitor (September 19, 1993)

© David Scott, 2005. All rights reserved.