By David Scott

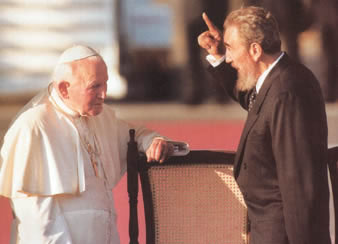

Cuban President Fidel Castro used the Jan. 21–25 papal visit to burnish his self-image as champion of the wretched of the earth, welcoming Pope John Paul II in a speech laced with anti-imperialist rhetoric and stock Marxist critiques of the Catholic Church.

Cuban President Fidel Castro used the Jan. 21–25 papal visit to burnish his self-image as champion of the wretched of the earth, welcoming Pope John Paul II in a speech laced with anti-imperialist rhetoric and stock Marxist critiques of the Catholic Church.

But, as more than one observer noted, throughout the week Castro looked like a stranger in his own land. With every word and gesture, Pope John Paul II seemed to underscore that alienation—patiently building his moral case that communist Cuba, cut off from its deep Christian roots, was a country severed from its very soul.

He came calling himself a “pilgrim of love.” And from the moment he pressed his lips against the plate of native soil offered him by four Cuban children, the Pope was planting the spiritual seeds for a new, post-communist Cuba.

In his arrival speech, the Pope answered Castro’s tirade by recalling the first plantings of the faith in the New World 500 years ago. Christopher Columbus, the Pope noted, called Cuba “the most beautiful [place] that human eyes have seen,” and the first cross that he placed in Cuban soil is still venerated in a parish in Baracoa, on the eastern edge of the island.

Throughout the visit, the Pope quoted religious words from Cuba’s founding fathers and national heroes in an effort to recall, for a generation raised under a strict atheist regime, that “Cuba has a Christian soul.”

After praying at the tomb of Father Felix Varela, the Pope reminded cultural leaders and Communist Party functionaries that the 19th-century independence leader was “the veritable father of Cuban culture” and is “considered by many to be the foundation stone of the Cuban national identity.”

“He was the first to speak of independence in these lands,” the Pope continued. “He also spoke of democracy, judging it to be the political project best in keeping with human nature.”

In a dramatic moment in his final homily, delivered to 150,000 people gathered at a Mass in Havana’s Plaza of the Revolution, the Pope quoted Catholic poet and freedom fighter Jose Marti’s eloquent defense of the “pure selfless, persecuted, tormented, poetic and simple … religion of the Nazarene.”

In an obvious and pointed rebuke to the regime of the Cuban president who was seated in the first row, the Pope added Marti’s warning: “An irreligious people will die, because nothing in it encourages virtue.”

During his first Mass in Cuba, at Santa Clara, the Pope surveyed the moral wreckage of three decades of atheist communist rule.

He decried Cuba’s rampant abortion and divorce rates, the denigration of motherhood and children in “economic or cultural systems which, under the guise of freedom and progress, promote, or even defend an anti-birth mentality.”

The Pope urged Cubans to return to the traditional family values of their Creole heritage—when families, “whether in poverty or plenty,” were marked “by a desire for a better world and above all, by greater faith and trust in God.”

The Pope likewise called for restoration of the Church to its rightful place in Cuban society, a place from which to proclaim the Gospel and defend human dignity.

“When the Church demands religious freedom, she is not asking for a gift, a privilege or a permission dependent on contingent situations, political strategies or the will of the authorities,” the Pope told Cuba’s bishops. “Rather, she demands the effective recognition of an inalienable human right … a right belonging to every person and every people.”

The Church, the Pope insisted in talk after talk, desires no political pulpit. But it does have the right to run its own schools, newspapers, and media outlets, as well as to perform works of charity and evangelization. In a constant refrain, the Pope warned that without a strong Church, Cuban society can never hope for renewal or lasting justice.

“History teaches that without faith, virtue disappears, moral values are dulled, truth no longer shines forth, life loses its transcendent meaning, and even service of the nation can cease to be inspired by solid motivations,” he said during a Mass in Santiago. He underlined his point with the words of another Cuban patriot, Antonio Macea: “He who loves not God, loves not his country.”

In nearly every appearance, the Pope criticized subtly or overtly what Castro’s revolution had done to insult human dignity. He rejected the communist system in which, “ the scale of values is inverted, and politics, the economy and social activity are no longer placed at the service of people,” and in which, “a man … becomes the object and not the subject of his social, cultural, economic and political surroundings.”

His most blunt critique came in his farewell speech, where he blamed Cubans’ “material and moral poverty” on “unjust inequalities, in limitations on fundamental freedoms, in depersonalization, and the discouragement of individuals.”

No doubt wary of the way the newly liberated communist nations of Eastern Europe rushed to embrace lassiez-faire capitalist models, the Pope warned Cubans of “the idols of the consumer society.” He decried an international monetary system on which a “small number countries [are] growing exceedingly rich at the cost of the increasing impoverishment of a great number of other countries.”

While communists treat men and women “as mere producers with little room for the exercise of civil and political liberties,” the Pope cautioned against rival models that see people “simply as consumers,” and in which “freedom is understood in a very individualistic and reductive sense.”

John Paul stressed that he had come to preach the Gospel, not to propose “an ideology or a new economic or political system.” But he promised that in this Gospel, faithfully lived, Cubans would find true freedom, happiness, and justice.

“If the Master’s call to justice, to service, and to love is accepted as good news then the heart is expanded, criteria are transformed, and a culture of love and life is born. This is the great change society needs and expects,” he declared during the final Mass in the Plaza of the Revolution.

The 77-year-old Pope, preacher of the peaceful collapse of communism in Europe, was asking the Cuban people to believe in his kind of revolution—not one achieved at the barrel of a gun, but one to be fought in every heart, though “love, commitment, self-sacrifice, and forgiveness.”

There is no telling how the 71-year-old Castro will respond to the Pope’s appeal to allow room for Jesus Christ “ to come into your lives, into your families, into society.”

In 1953, Castro published a defense of his first revolutionary bid, entitling it, “History Will Absolve Me.” And all his remarks during the papal visit appeared to be variations on this theme.

But John Paul’s historic visit should be a reminder that, in the end, it is not the tribunals of history or even of the Cuban people that Castro will have to answer to.

As the Pope told reporters traveling on the plane to Cuba, both he and Castro are “in the hands of Providence. The history of the world is not only the history of people and states, but is also a history of salvation.”

Originally published in Our Sunday Visitor (February 8, 1998)

© David Scott, 2009. All rights reserved.