By David Scott

States once executed criminals in the center of the town at high noon. Today, they do it in secret, at midnight, behind brick walls fortified with barbed wire, electrified fences and machine gunners.

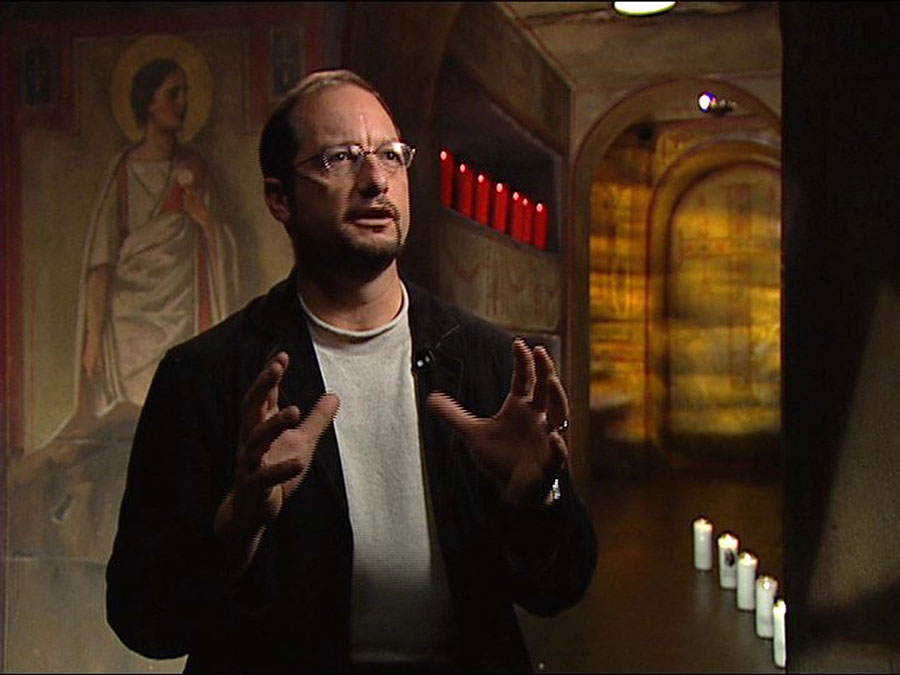

In his recent book, The Execution Protocol (Crown, $20), Stephen Trombley scales the walls thrown up around the capital punishment industry in America. What he finds, he says, is “another America, a netherworld where men wait for their appointment with death, and where another group of men wait to execute them.”

An author and filmmaker, Trombley here documents a year he spent with Fred Leuchter, inventor of the lethal injection machine, and with death row inmates and staff at Potosi Correctional Center, an execution site in rural southeast Missouri.

The result is a disturbing if flawed and incomplete book, but one that will remain an important chronicle of a bizarre American subculture of death, a place where, as Trombley notes, “everybody has one thing in common: They have taken human life.”

Unfortunately, Trombley’s interviews with the condemned on death row are not especially personal or revealing. Part of the problem is that he relies to heavily on jailhouse lawyer-types whose views often sound like a parody of stale anti-death penalty speechifying.

But he excels in showing how “ordinary” life seems in the executioners’ world. For example, though he makes a living by designing and selling killing machines, Fred Leuchter comes across as the guy next door. He likes computer games, has an obese mutt of a dog named Rex, a wife who drinks Diet Coke, and enjoys old television shows like “The Saint” and “Highway Patrol.”

After work, members of the Potosi execution team shoot pool and drink beer; they even invite Trombley to join them and their spouses on one of their regular weekend fishing trips. For them, killing killers is all in a day’s work.

“Once an execution is over, people just basically go home,” one of the team tells Trombley. “Normally my wife is up, and we sit down, we talk and discuss, and I go to sleep. I don’t have a problem going to sleep after an execution.”

The death penalty, it seems, is not a moral question but an accepted fact of life for these executioners. Leuchter delights in his work as much as any craftsman. For him, creating an efficient method of execution is a medical and entrepreneurial challenge.

“The human body is designed not to be destroyed,” he explains. “The minute you stop the heart, it has a mechanism for restarting the heart. And heart death is the key in all executions. So we have to design a system that, after if destroys the brain, it destroys the heart.”

Like any good entrepreneur, Leuchter tries to make products that people need. He invented his “modular lethal injection system”—a hospital bed equipped with a series of intravenous lines—as a faster and easier way for states to administer death. Death takes 4.5 minutes by lethal injection. And unlike other models, his brand of electric chairs is custom-crafted so that the broiled flesh of victims doesn’t stick and pull off when his customers remove the body from the chair.

Leuchter provides on-site training and services what he sells. His lethal injection system retails for $30,000 (lethal chemicals are extra, about $600–700 per killing). His electric chairs go for $35,000 a piece; gas chambers cost $200,000 (plus $200 for cyanide gas).

For customers who don’t have as much space, Leuchter offers a fully equipped, mobile execution site for around $100,000.

“I don’t get rich with what I do,” Leuchter confides. “I make a decent living. I have a 20 percent markup on my equipment, and I think that’s more than fair.”

Conscience Protocol

Leuchter has also gained some notoriety for his work as a consultant. In 1988, he inspected the Nazi prison camps at Auschwitz, Birkenau, and Majdanek and delivered this expert opinion: “the evidence is overwhelming: there were no execution gas chambers at any of these locations.”

The inspections and the report were funded to the tune of $30,000 by Ernst Zundel, a pioneering figure in the Holocaust denial movement, and Leuchter’s “expert” testimony has helped fuel the movement.

But he seems genuinely surprised by the turmoil caused by his report. He tells Trombley that he believes “probably there was a Holocaust,” and that the Nazis were “nasty bastards,” but that scientific evidence does not support the existence of gas chambers at those three sites in Poland.

His involvement in the controversy casts an eerie shade over this work in the “routinization” and professionalization of the U.S. execution system.

The execution process that Trombley details is governed by an elaborate “execution protocol” developed by Missouri prison officials. The protocol breaks down the process of executing someone into a set of essential jobs and divvies up those jobs among team members.

Detailed and all-encompassing, the protocol “ritualizes every moment of the deathwatch and execution process from the time the governor signs a death warrant to the time a body is removed from the death chamber.” Trombley reports.

While the protocol lends an aura of military precision to the execution process, it also serves as a sort of absolution rite or tranquilizer of the conscience, Trombley observes.

The protocol keeps everyone’s mind “off the grisliness of their task” by allowing each team member “to focus on his or her part of the process rather than the whole process and its result,” he explains. In that way, the protocol aims to evenly distribute moral culpability so that no one feels individually responsible for the killing.

And all the evidence indicates that this protocol works. Reporting on a survey of team members, the prison psychologist tells Trombley that “the overall consensus was that the problems expected, i.e. stress, guilt, depression, etc., did not occur following the executions.”

Adds another execution team member: “When you’re in preparation of actually taking a human life, you have to look into your own self and say, ‘I’m an instrument of the state. I have a job to do, and I choose to do it. I never killed anybody, but this individual has been convicted thereof. And so this is the ultimate penalty that will be carried out, and we are the instruments whereby it’s carried out.’”

As if smelling a hypocrite, Trombley grills the Baptist minister who serves as Potosi’s chaplain, inquiring how the chaplain “reconciles executions with Christian belief.” For his part, the chaplain proves to be the insensitive, spiritually muddled man that the inmates accuse him of being.

But aside from that chaplain, Trombley is not brave enough or interested enough to ask about the religious beliefs or moral convictions of the others he interviews. It is not that he doesn’t have plenty of opportunities. In numerous instances, his subjects bring up questions of faith or morals; Trombley simply ignores them.

In passing, he mentions that the Leuchters’ home has a small area devoted to the Blessed Virgin Mary, complete with a small statue of Mary, a tiny altar, votive candles and artificial purple lilies. But he never wonders why the Leuchters might have a special devotion to Mary or how their faith might relate to Leuchter’s work inventing efficient killing machines.

Prayer and Death

The execution protocol provides for a prayer service for the execution team and prison staff just hours before the execution. But Trombley never asks why or what an executioner might pray about.

Also, the Potosi warden says that he exempts from execution duty any prison staffers who object to capital punishment on moral grounds. Trombley doesn’t interview any of those conscientious objectors, nor does he asked members of the execution team how they feel about doing a job that others find morally reprehensible.

At still another point, the warden says that the wife of one executed man keeps telling him that he will have to answer to God for his role as head executioner. One waits in vain for Trombley to ask the warden, “Well, what do you believe? Are you going to have to give an accounting or do you feel that you are blameless in the eyes of God?”

Trombley says that he set out to present an objective look at America’s “execution protocol.” But by failing to ask moral and religious questions, he winds up with an account that is heavily biased in favor of an unnatural, wholly secular viewpoint.

What emerges from his book is the standard secularist view that religion and morals have no legitimate role in the workplace or in the making of public policy. But even the evidence he himself gathered shows that morality and religion play a part in the lives of the executioners and the condemned.

Trombley’s interview with the Potosi chaplain provides a frightening glimpse at what happens when God is left out of the way people approach their work and their society. The chaplain feels that in helping the state execute people he is merely following Jesus’ counsel to render unto Caesar what is Caesar’s.

“My personal belief is, and I base this biblically … that the death penalty is not a spiritual issue,” says the chaplain. “It’s not a Christian issue. This is our government, it’s what our government has said we will do and we will abide by that. …We should render unto the higher authorities and higher powers over us.”

Missing from the chaplain’s view is any sense of the mystery and irony that Christianity started with the execution of an innocent man or that the first Christians were martyred precisely because they refused to accept that the state was a higher authority than God.

More chilling is the chaplain’s belief that he is an instrument of the state and that the state, not God, is the final judge on whether a person’s life has value or is redeemable.

That is the still unexplored moral logic of the execution protocol, a deadly logic that connects Fred Leuchter and the Potosi prison to Auschwitz, abortion clinics, and wars of ethnic cleansing.

Originally published in The Evangelist (May 6, 1993)

© David Scott, 2009. All rights reserved.