In the view of Franciscan Father James Goode, the freeways that arch above America’s inner cities are a metaphor for the profound alienation of the races and the nation’s flight from the problems of the black ghetto.

As the country’s leading black Catholic evangelist, Father Goode has, in the past 20 years, preached in the violent, poverty-torn heart of nearly every major American city.

He brings the good news to neighborhoods where skeletal buildings, gutted and boarded up, mark places where people once worked, worshipped and went to school. And wherever he is, he is haunted by the concrete and steel ceilings squatting overhead—the freeways leading to the suburbs.

“As the years go by, we have tried to build freeways to bypass these poverty areas,” Father Goode said in a recent interview. “Now we’ve reached a point where we’ve got to take the side road. We can’t escape it for too long – we’re going to have to face the reality.”

The reality of black inner-city life once more exploded into the national conscience in late April, when violence erupted in cities across the country after four white Los Angeles policemen where acquitted on charges that they brutally beat a black criminal suspect, Rodney King.

The urban uprisings, and the national soul-searching about race and poverty they have evoked, form the framework for this week’s National Black Catholic Congress, July 9–12, in New Orleans.

In addition to its importance for the Church, the meeting could possibly have national implications—America’s two million black Catholics now make up the third-largest religious grouping of blacks in the United States, following the Baptist and Methodist denominations.

The riots were a “wake-up call” to a society and Church that only grudgingly has opened its eyes to growing black poverty and the persistence of prejudice, according to Father Michael Pfleger, who has spent nearly 20 years in Chicago’s slums as pastor of St. Sabina’s Church.

He and other Catholic leaders spoke with a sense of urgency about the need for political remedies and renewed moral commitments. But they expressed fear that politicians and Church leaders still do not understand the gravity of the hour.

Two decades after the civil-rights movement, many Americans—including many Catholics—seem morally exhausted, they said, no longer sure that whites and people of color can live together and share in the country’s freedom and prosperity.

American Dreams

“The reality is that there are hundreds of thousands of African-Americans, especially African-American males, who are not sharing in the American dream and have no hope of sharing in it,” said Bishop John Ricard, S.S.J., auxiliary of Baltimore, one of 11 black U.S. bishops.

Americans did share in the collective experience of watching the videotaped beating of Rodney King as it was repeatedly broadcast on television. But it has proved harder to dramatize and stir empathy for the everyday struggles of the black underclass to which Rodney King belongs.

Broken families are the rule, not the exception, in the drug-infested Bayview-Hunter’s Point section of San Francisco where Father Goode serves as pastor of St. Paul of the Shipwreck Church.

More than half the children in St. Paul’s elementary school are raised by grandparents or other relatives. It’s not uncommon for Father Goode to help women who have been abandoned by unemployed husbands or lovers.

“That we in the inner city have a moral problem is a fact,” said Jesuit Father Fernando Arizti, associate pastor of St. Brigid’s Church in South Central Los Angeles.

Referring to the confluence of fatherless children, unwed mothers, drug abuse, crime and poverty in the slums, he acknowledged, “All the spiritual values are down the drain; there’s so much immorality.”

But he insisted that apportioning moral blame has little meaning in neighborhoods where people feel stripped of dignity and self-respect by the daily battle to survive.

“To have the moral values, first you have to have a person. We have forgotten about the person when we think about the oppressed and the poor,” he said.

In urban parish talks around the country, Georgetown University theologian and black Catholic activist Diana Hayes urges blacks to overcome the crippling feeling that they are helpless victims of a cruel and racist society.

She does not deny that urban blacks face an imposing array of institutional forms of racism—particularly from banks and insurance companies which too often will not do business with them because of the color of their skin.

While they fight for equal opportunity, Hayes says that blacks need to return to the days when they started their own businesses and used their money to build up their own communities.

“Too many of us—especially those in the underclass, the welfare dependents—are expecting handouts,” she said. “If we’re going to get anywhere, we’re going to have to do it for ourselves. We can’t expect others to do it for us.”

Black Catholic leaders say their message of religious faith and self-help is taking root. One shining example was a recent rally of some 1,000 fathers and other men in the Crenshaw district of South Central Los Angeles. Father Arizti organized the gathering, working in tandem with neighborhood churches and the local branch of the Nation of Islam.

“The event was ignored by the media,” he complained. “But there are so many fathers here who are role models for African-American youth. There’s a lot of desire to change things here and a whole lot of beautiful things happening. The media’s just bringing the bad news.”

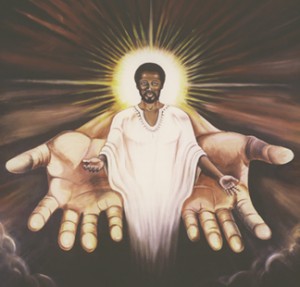

Since the race riots of the mid-1960s, Father Arizti has been painting what he calls “Catholic icons” for the black community. The Mexican-born Jesuit’s huge murals grace parishes and buildings from Washington to Chicago, from Brooklyn to Watts.

Father Arizti’s mural, “Lord of Watts”—a huge, black Jesus with His arms thrown open to embrace the blighted cityscape of Watts—is seen as a tribute to the persistent faith of America’s black inner-city Catholics.

“I see him in the streets, in the senior citizens, in the shut-ins, in the children when they’re playing,” said Father Arizti. “I see him everywhere I go. For me, that is Jesus—alive in the streets. I see him suffering; I see him laughing; I see him playing; I see him dying. I see his resurrection, too, in the Hispanic kids and black kids who have started coming to St. Brigid’s to meet each other and learn how they can live together.”

Resurrection was in the night air in San Francisco recently, as Father James Goode, pastor of St. Paul of the Shipwreck Church, led a ragtag Marian procession through the streets of Bay View/Hunter’s Point.

The evening sky was lit a dusky rose as dozens of black Catholics and others held aloft candles and lifted their voices in praise to Our Lady of Perpetual Help.

This freedom march of faith, Father Goode said, was an effort to consecrate the streets and reclaim them from sin, poverty, violence, and racism.

Racial Healing

On the other side of the country, in Brooklyn, N.Y., Catholics report small but encouraging success in healing the deep breach between the city’s blacks and whites.

In 1989, years of resentment spilled over when Yusaf Hawkins, a black youth from the city’s Bedford-Stuyvesant quarter, was killed by white youths from the Bensonhurst section.

Earlier this year, there was a meeting between black parishioners of Bedford-Stuyvesant’s Our Lady of Victory Church and whites from St. Dominic’s Church in Bensonhurst.

For Gertrude Guidry, a Louisiana-born great-granddaughter of slaves and veteran of a half-century of interracial dialogue in Brooklyn, the encounter and plans for future meetings are a tentative first step toward dispelling the ignorance and lack of social contact that lies at the heart of black-white tensions.

Black Catholic leaders hope that the Lost Angeles riots will move the Church to redirect its moral energies and the resources of its schools, charities and hospitals to inner-city needs.

Bishop Ricard points to the promise of efforts like the Nehemiah Housing Project in Baltimore. There, the archdiocese brokered a financial partnership with local religious orders, other denominations and federal and local governments, to build 300 units of affordable housing for low-income persons in the Baltimore slums.

On the other hand, Father Goode is worried by the accelerating numbers of parish and school closings in cities across the country. The Church has to be wary of being infected by the “pull-yourself-up-by-the-bootstraps mentality” that prevails in much of the current debate over social policy, he said.

Now, more than ever, there needs to be a strengthening of Catholic schools in the inner city, no matter what the cost, Father Goode and Diana Hayes argued. A vital Catholic school system could be a bulwark against urban despair and a beacon that guides the building of families and new communities.

As Father Goode warned: “These problems are not going to go away. What happens to the Church in the inner city very much affects the suburbs, and we cannot just escape that. If we are part of a Church or a diocese, if we are talking about building our faith, we can’t just sell our home, move away and say, ‘We don’t have that problem anymore.’ Where will we continuously run, when we are a part of each other?”

Originally published in Our Sunday Visitor (July 5, 1992)

© David Scott, 2005. All rights reserved.