The most insightful book of this election year has been the best-selling Bobos in Paradise (Simon & Schuster, 2000).

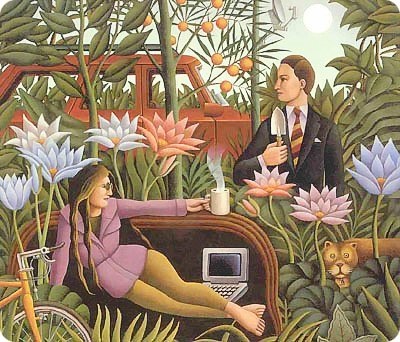

David Brooks, a self-confessed “Bobo” who writes for the conservative journal, The Weekly Standard, argues that today’s ruling elites—the dot-com millionaires, the celebrity pundits and media empire-builders—along with the millions of educated beneficiaries of our booming “information economy,” constitute a new social class, which he calls “Bourgeois-Bohemians,” or Bobos for short.

What he means is that in their manners and beliefs, these people combine the 1960s “bohemian” values of self-expression, pleasure-seeking and distrust of authority, with the “bourgeois” values of the conspicuously consumerist, greed-is-good ’80s.

Studying their beliefs, buying habits and even their mating rituals, Brooks offers a telling picture of the folks who are in the driver’s seat of turn-of-the-century America. These are the people who are shaping our society through the businesses they start, their reporting of the news, the movies, TV shows and ads they produce, and the political platforms they write and vote for.

Studying their beliefs, buying habits and even their mating rituals, Brooks offers a telling picture of the folks who are in the driver’s seat of turn-of-the-century America. These are the people who are shaping our society through the businesses they start, their reporting of the news, the movies, TV shows and ads they produce, and the political platforms they write and vote for.

As Brooks notes with some approval, Bobo politics is non-ideological. It’s live-and-let-live, with no mean people or extremists allowed. Bobos aren’t looking to be called to higher ground; they don’t expect an America that is a shining city on the hill. They want a peaceable middle ground where everybody can just get along.

The political slogans of recent years—“compassionate conservatism,” “getting beyond tired old labels of left and right that just divide us,” “a kinder, gentler nation,” “practical idealism”—both express and speak to the soul of the Bobo.

Bobo religion is more about “seeking” than following, in Brooks’ telling. The Bobo doesn’t ask, “What does the Lord or the Law require?” The Bobo asks, “How does this belief meet my needs?” Bobos aren’t looking for orthodoxy, but what Brooks calls “flexidoxy.”

They want to feel part of a community, to have some roots. But they’re wary of religions that claim to have the “whole truth,” or people whose moral code is “too inflexible.”

Here is Brooks’ helpful summary of the social teaching of this new class:

“They tolerate a little lifestyle experimentation, so long as it is done safely and moderately. They are offended by concrete wrongs, like cruelty and racial injustice, but relatively unmoved by lies or transgressions that don’t seem to do anyone obvious harm. … They aim at decency, not saintliness. … In short, they prefer a moral style that doesn’t shake things up, but that protects the status quo where it is good, and gently tries to forgive and reform the things that are not so good.”

Brooks adds with a hint of caution, “This is a good morality for building a decent society.”

But is it, really? Can an individual or a people really be sustained without some sense of higher purpose? Can a society really survive and thrive by splitting every difference?

Boboism strikes us as the creed of a sated people—radical-individualism lite.

Boboism assumes that there is nothing left worth fighting for—no larger personal obligations than responsible consumerism and smiling at the checkout clerk, no higher political obligations than how to spend a budget surplus.

It’s a deceptively attractive ethos for an era of unbelievable abundance. And it will probably last until the money runs out.

Originally published in Our Sunday Visitor (August 20, 2000)

© David Scott, 2009. All rights reserved.