Sometimes a book’s importance depends more on who is reading it and talking about it than what it actually says.

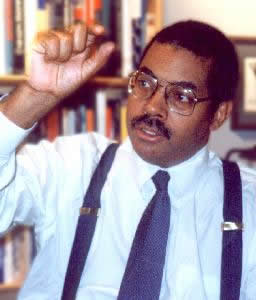

That explains the widespread celebration of Yale University law professor Stephen Carter’s new book, The Culture of Disbelief: How American Law and Politics Trivialize Religious Devotion (Basic Books, 1993).

Carter’s book got its best plug from President Clinton, who hosted an interfaith prayer breakfast at the White House in late August, and urged his guests to read it.

And in the ensuing months, Carter has been hailed as a new voice of calm and compromise in the wrenching national debate over religion, morals and culture.

But one has to look at all the solemn and respectful discussion about Carter’s book with raised eyebrows. Because, really, he is saying nothing new.

His basic message—that America’s moral and democratic future is jeopardized by the exclusion of religion and religious values from the nation’s political and cultural debates—has been a staple criticism made by Catholics and other religious commentators for years. Like them, Carter, too, is worried about the moral health of a society where the mention of God or faith in public is often an invitation to scorn, ridicule and perhaps a lawsuit.

His basic message—that America’s moral and democratic future is jeopardized by the exclusion of religion and religious values from the nation’s political and cultural debates—has been a staple criticism made by Catholics and other religious commentators for years. Like them, Carter, too, is worried about the moral health of a society where the mention of God or faith in public is often an invitation to scorn, ridicule and perhaps a lawsuit.

What makes Carter’s take on this situation new and provocative is the fact that he is not a cultural or political conservative, but a self-professed “liberal,” as well as a devout Christian, an Episcopalian to be exact.

He takes pains to prove that his views never stray from the reigning liberal orthodoxy: He is “pro-choice,” thinks homosexuals should have equal civil rights, supports women priests, opposes prayer in public schools, and is scared of the “Christian right” and its agenda.

But he also wants people to know that he and his wife send their children to parochial school and that he is alarmed by the way believers are excluded from crucial national debates on abortion and euthanasia.

“There is much depressing evidence,” he warns, “that the religious voice is required to stay out of the public square only when it is pressed in a conservative case.”

Carter clearly wants to be seen as staking out the middle ground. And in many ways his is a good book. He seems sincerely concerned that he and his fellow elites—in the schools, the courts, the legislatures and in the media—have gone too far in their zeal to separate church and state.

Without religious and moral participation, he argues, American politics will rapidly spiral into “tyrannical majoritarianism, in which every aspect of society is ordered as 51 percent of the citizens prefer.”

Such a state of affairs—in which what is good or bad for the country and its people is decided not by moral consensus but by simple majority vote—should worry all Americans regardless of their political beliefs, as Carter points out.

The Culture of Disbelief is persuasively argued, and it will no doubt appeal to Catholics and others who want to see the Church’s thinking on social concerns more widely appreciated by politicians and the makers of public opinion.

But for all his aspirations to moderation and compromise, Carter has written a largely one-sided account, one that in fact reflects the problems of disbelief that he diagnoses in the culture.

As an example, while he claims to be writing about the way American institutions have “trivialized” religion, he reserves his most pointed direct criticisms for cultural conservatives and Republicans.

That is not to say that most of his specific criticisms of Republicans and conservative religious excesses are not right on the mark. But it is disturbing and revealing that Carter has a hard time finding fault with any areas of the liberal or Democratic agenda.

By his own standards, for instance, the 1992 Democratic National Convention should have been a devastating case study of how religion is trivialized and demeaned in American political life.

There, the party that preached diversity and inclusion (and provided a broad platform for the handicapped, homosexuals, women and minorities) refused to allow religiously motivated pro-life Democrats, such as popular Pennsylvania Gov. Robert Casey, to address delegates.

Carter says nothing about this. Yet he repeatedly criticizes delegates to the 1992 Republican National Convention for their blatantly political use of religious rhetoric, and even goes so far as to “tremble for their souls.”

In the same way, while he criticizes conservatives for using theology to mask their phobias and prejudices, Carter leaves unquestioned some clearly questionable assumptions of liberal theology.

If he was truly interested in dialogue and compromise, he could have examined honestly whether there is a religious foundation for his own positions on “reproductive choice,” “group rights,” or “inclusivity.”

Even when one moves to the heart of his argument—namely that America is turning religion into a trivial pursuit, a “hobby” as he likes to call it—one finds him working hard not to offend his colleagues and peers. The problem, he insists, is indifference, not hostility, to religion. He dismisses without much considering the evidence, the arguments of those who believe that this culture is openly at war with religion.

These deficiencies betray something of Carter’s real agenda in The Culture of Disbelief. For this book is, at the bottom, a plaintive cry for liberals to reclaim “religion” and religious language lest they lose the culture wars to conservative Christians.

“American liberals,” he says at the very outset, “have made a grievous error in the flight from religious dialogue.” Near the end of the book, he warns that unless liberals respond to widespread fears that America is “spinning out of control,” many religious Americans will run “rushing into the waiting arms of the next demagogue.”

In trying to make religion palatable for a skeptical liberal audience, he points to the religious inspiration of the 1960s civil-rights and anti-war movements. But in the process, Carter throws out the spiritual and transcendental dimension of faith.

For Carter, the Church does not exist to proclaim to the world the truth about Jesus and his promise of salvation. “Churches,” he says instead, “should be moral forces in the political world and I am not sure that they do much good if they are anything else.”

In his fear of the religious right and in his zeal to rally liberals to his cause, Carter reduces religion to politics.

The Culture of Disbelief clearly strikes a chord. At a time when many Americans, from the president on down, are worried about the apparent decline of basic values and widespread confusion about what is right and what wrong, Carter offers a solution.

But the causes of this country’s problems run deeper than his political analysis would suggest. At the root is a loss of a common idea that has held Western civilization together for centuries—the belief that God is the source and the ultimate goal of existence.

Stephen Carter notwithstanding, this country’s problems cannot be solved by more moral public policies or more inclusive political debate. Politics can break men’s bodies or lift them up in times of need, but politics cannot offer salvation, which is ultimately what Americans, and everyone else, is looking for.

Originally published in Our Sunday Visitor (November 7, 1993)

© David Scott, 2009. All rights reserved.