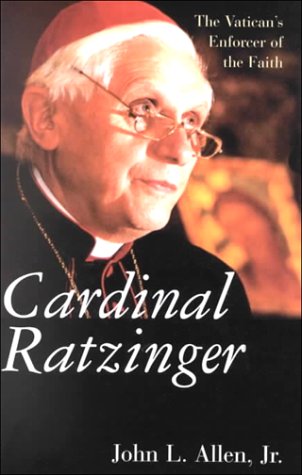

Cardinal Ratzinger: The Vatican’s Enforcer of the Faith

Cardinal Ratzinger: The Vatican’s Enforcer of the Faith

John L. Allen, Jr.

Continuum, 2001

Book Review

Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, head of the Vatican’s Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, is a rigid totalitarian who “sold his soul for power.”

Committed to a rule-bound, abstract notion of Christianity, Pope John Paul II’s right-hand man has spent 20 years in Rome providing theological cover for capitalists who exploit the poor, bigots who oppress women and gays, and zealots who make war in the name of God.

That’s the summary judgment John L. Allen Jr. makes against Ratzinger in this new biography of the second-most powerful man in the church.

As Rome correspondent for the National Catholic Reporter, self-styled voice of “progressive” Catholicism, Allen’s reporting is usually competent and fair-minded. But this book is neither. Allen comes not to understand and explain Ratzinger but to indict him.

It’s too bad, because Ratzinger’s story is in many ways the story of the Catholic Church in the latter days of the 20th century.

It’s a story filled with complicated issues, colorful players, and high stakes. Against the backdrop of seismic upheavals in the Church and the world, a brilliant youngish academic (Ratzinger was one of Europe’s top theologians and an influential insider at the Second Vatican Council), is brought to Rome by an equally brilliant and youngish pope.

Almost immediately, he finds himself locked in one theological and cultural mudfight after another. He loses friends, incurs the scorn of secular elites, while all around him his co-religionists take up sides and cudgels — some hailing him as the faith’s great defender, others crowning him prince of a new Dark Ages.

But instead of letting this tale unfold in all its ambiguity and complexity, Allen burdens himself with prosecuting the case for Catholic “progressives” who feel they’ve been victimized under Ratzinger’s tenure.

And in his zeal for conviction, Allen loses the trust of the undecided reader early on. You get the feeling as you read this book that you’ve wandered onto the field of some bloody intramural score-settling — as Allen does unto Ratzinger what he claims Ratzinger has done unto Allen’s progressive friends.

‘Ecclesiastical Totalitarianism’

Most of the book reads like yesterday’s left-wing Catholic news, as Allen spends long chapters rehashing Ratzinger’s pivotal role in debates dating back to the 1970s over liberation theology, women’s ordination, homosexuality and religious pluralism.

Allen wants us to believe that the German-born Ratzinger came to his current job carrying psycho-biographical baggage from his childhood under the Nazi regime. “Having seen fascism in action, Ratzinger today believes the best antidote to political totalitarianism is ecclesiastical totalitarianism,” Allen writes.

In a frustratingly contentious chapter on Ratzinger’s youth, Allen tries hard to make the evidence stick.

Digging for bad roots in the Ratzinger family tree, Allen unearths a priest-uncle who was an anti-Semite. Then he notes that Ratzinger once failed to denounce his uncle’s Jew-hating in a four-sentence reply to an interview question about him.

For Allen, this is a telltale omission: “Ratzinger cannot be ignorant of his uncle’s anti-Judaism….There is no basis for suspecting that Joseph Ratzinger harbors any of his great uncle’s sentiments about the Jews — indeed his public record is full of denunciations of anti-Semitism — but Jews might be saddened at his silence here nevertheless.”

Never mind that the uncle died nearly 30 years before Ratzinger was born. And neither Allen nor his editors seems troubled by the fact that he has no evidence to suggest the cardinal was even aware of his relative’s vile views. For Allen, his alleged “silence” is good enough to cast reasonable doubt on the sincerity of what he must admit is Ratzinger’s lifelong defense of Jews and Judaism.

Allen takes the same tack in trying to establish that Ratzinger was somewhere between indifferent to and morally complicit in the Holocaust.

That’s a hard case to make, especially since Ratzinger was only six years-old when Hitler came to power, never attended the Hitler Youth meetings required of all German adolescents, and was an unwilling conscript in the Nazi army at the age of 16. (He deserted two years later, at the end of World War II, having never fired a shot in defense of the Reich.)

Nonetheless, Allen damns Ratzinger for not protesting the deportation of Jews from his hometown and for not taking part “in any kind of resistance” against the Nazis—as an adolescent.

By the time Allen moves to Ratzinger’s career at the Vatican, the reader has learned that fact, innuendo, circumstantial evidence, and insult from interested parties are of equal evidentiary value for Allen.

We hear of rumors that Ratzinger ordered a liberal nun’s books to be burned, and that a suicide note from a gay man blamed Ratzinger’s Vatican for his anguish. It doesn’t matter that the rumors were false, that the suicidal man had never met Ratzinger. Allen dutifully logs all of it into evidence anyway.‘Clearly Ill, Violent’

Allen quotes copiously and uncritically from Ratzinger’s opponents, no matter how outrageous their rhetoric or unsubstantiated their charges. Liberal theologian Hans Kung, censured for denying papal infallibility, compares Ratzinger to a KGB torturer. Another disciplined cleric, the New Age priest (and lately, Episcopalian convert) Matthew Fox, describes Ratzinger as “clearly ill, violent, sexually obsessed.”

The reader might excuse such sallies as clumsy efforts to revive a flat-lining narrative. But there’s a constant hectoring in his tone, not to mention a contrived aura of clairvoyance, as Allen tries to convince us that he has a psychological bead on his quarry’s motives and intentions.

At every turn, Allen knows how events “must seem” to Ratzinger, and he can tell us in any given situation “ultimately what is at stake for Ratzinger.” That, though he never once was granted an interview with Ratzinger and, by my count, only talked to three or four people who know Ratzinger and actually respect him.

Allen also claims to have an authoritative finger on the pulse of such disparate groups as “most homosexuals,” “most Catholic theologians,” “most women,” and apparently a subset of the last, “educated and self-aware women.” He informs us that all these groups are aggrieved victims of Ratzinger’s policies at the Vatican. But again, neither Allen nor his editors seems bothered by the fact that there are no polls or other evidence to support his sweeping generalizations.

Doubts about Allen’s reliability as a reporter turn to outright skepticism when at one point he starts swinging madly, blaming the Catholic Church for the roving gangs in Brazil that beat up gays and for being “a carrier” of “patriarchal values.”

Such little ecstasies of indignation are arguably entertaining. However, Allen doesn’t seem to know that there’s a difference between bad protest poetry and responsible journalism. It may be that ancient Catholic beliefs really do lead to violence against gays and women. But though he shouts himself hoarse on these issues, Allen doesn’t bring any proof to the table. Ratzinger’s fatal flaw, according to Allen, is that he lacks sufficient reverence for “the historical Jesus.”

This is Allen’s theological trump. He never cites a line of the Bible to support his theory, but he does assure us repeatedly that he knows the real Jesus, and the real Jesus wouldn’t like the way Ratzinger does his job.

Again, Allen may have a point in asserting that Jesus would have handled disagreement and dissent from Church teaching differently than Ratzinger. But the reader of a purportedly serious book expects Allen to defend, or at least to explain, his understanding. Especially when he summons Jesus as his star witness against the accused.

But throughout this humorless and naively triumphalist history, Allen never questions his own assumptions or those of his fellow “progressives.” And he never really gets close to his subject and what motivates him. Instead of a biography of Ratzinger, Allen has produced a rap sheet, a book-length inquisition against the man he dubs “the Grand Inquisitor.”

Originally published by Beliefnet.com (January 2001)

© David Scott, 2003. All rights reserved.