Joseph Stella is remembered most for being one of America’s greatest modernist painters.

Man Ray’s memorable portrait, circa 1920, poses him belly up to a bar behind a bottle of beer and a Spanish guitar. With his broad-brim hat and his wise-guy smile, it’s the portrait of the artist as bard and bringer of new songs for a new world.

In his masterpiece, “The Brooklyn Bridge” (1939), Stella caught in steely shards of blue and white light the spirit of early 20th-century America—the youthful whir and hum of expectation, all the energetic potential of a people just starting to fashion a new machine-age world of metal and glass, electric dynamos, subways, and cinemas.

If “Brooklyn Bridge” evokes the stained-glass of cathedral windows, it’s because for Stella and contemporaries, notably the poet Hart Crane, the erected bridge was an almost godlike presence.

“Many nights I stood on the bridge,” Stella later wrote, “crushed by the mountainous black inpenetrability of the skyscrapers…shaken by the underground tumult of the trains in perpetual motion, like the blood in the arteries…now and then strange moanings of appeal from tug boats, guessed more than seen, through the infernal recesses below—I felt deeply moved, as if on the threshold of a new religion or in the presence of a new Divinity.”

But Stella had also seen the dark underbelly of this new “divinity” sprung from human ingenuity.

Coming to America in 1896 from a small mountain village near Naples, the 19-year-old Stella witnessed and preserved in burning charcoal portraits the suffering figures of his fellow immigrants—living in hovels, persecuted by “native-born” Americans, exploited in factories, mills and mines.

“A new Divinity, more monstrous—and cruel than the old one, dominates all around,” Stella observed. “We lose this sense of religion and terror and we realize the power [of] man… man, him, the Conqueror, claiming and seizing the Promethean fire.”

Perhaps it was that realization that led him to return to Italy in the 1920s, after the chaos and terror loosed by the first world war. There he aspired to a new art and a new mythology to go along with it—one borne of his Catholic heritage and the rhythms of the Italian highlands.

“I thank God for the good fortune to have been born in a mountainous place,” he wrote of Murano Lucano, his birthplace in the southern Italy. He called the mountains there “a familiar face that one meets on the balcony of one’s soul.” In the countryside, he felt “bathed in the holy water of baptism.”

He recalled, too, “the Mother church” he grew up in: “At Easter, the pealing of bells from its tower filled the air with its joyous echoing sounds.”

During this period, Stella went on a series of religious and artistic pilgrimages—to Siena, Florence, Perugia, Assisi and Ravenna. And he began for the first time to paint religious scenes, blending futurist techniques and brilliant Oriental colorings, with the popular sensibilities of Italian devotional art.

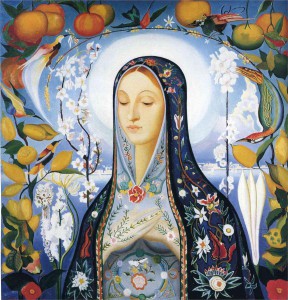

The result is nothing short of a glorious mystery, as reflected in last year’s under-appreciated exhibit, “Joseph Stella’s Madonnas and Related Works,” at the Snyder Fine Arts Museum in New York and the Snite Museum at the University of Notre Dame.

Stella’s Madonnas are exotic and ethereal, lavish and voluptuous, contemplative and fecund. In “Purissima” (1927), she is a queen come from the far east or a bride awaiting her betrothed in a tropical garden, flowers in her hair, feted by dazzling white swans.

In “The Virgin” and “Virgin of the Rose and Lily” (both 1926), she is a maiden most modest, eyes cast down and lips pursed, hands clasped over her breasts as she stands beneath a canopy of luscious ripe fruits and flowering vines.

While nobody would claim Stella as anything like an orthodox believer, there is something biblical, even liturgical, about his Madonnas. His is the Mary of the ancient litanies—the Spiritual Vessel and Mystical Rose, the Tower of Ivory and House of Gold, a Virgin Most Pure, a Queen of Angels, a Morning Star.

Stella probably never thought of them in this way. But today his Madonnas seem like annunciations of what he once described as “the reassuring smile of Divine friendship.”

It was a smile that in Stella’s time could be perceived only dimly and seems dimmer still today—when the Brooklyn Bridge is a relic and men’s Promethean powers yield works of even more breathtaking achievement and more startling cruelty.

Stella’s Madonnas capture a moment in one man’s search for blessed assurance. And in his desire to envision a world that is more than the sum of man’s ambitions or the works of human hands, the consummate modernist gave us futuristic icons of an ancient truth—the Immaculate Conception and the divine pledge of a new creation.

Originally published in Our Sunday Visitor (December 4, 1994)

© David Scott, 2003. All rights reserved.